Inside MODA’s New Exhibit THE HOODIE: Identity, Power, Protest with Dr. Regina Bradley

Few garments carry as much cultural weight as the hoodie. First created in the 1930s by the brand Champion to meet athletes' needs for warmth and durability, the hoodie slowly became a marker of style, anonymity, suspicion, and resistance—often all at the same time. In The Hoodie: Identity, Power, Protest, a new exhibition at the Museum of Design Atlanta (MODA), co-curators Dr. Regina N. Bradley and Dr. Laura Flusche examine the hoodie not just as a piece of clothing, but as a deeply political symbol shaped by race, class, geography, and history within the American South.

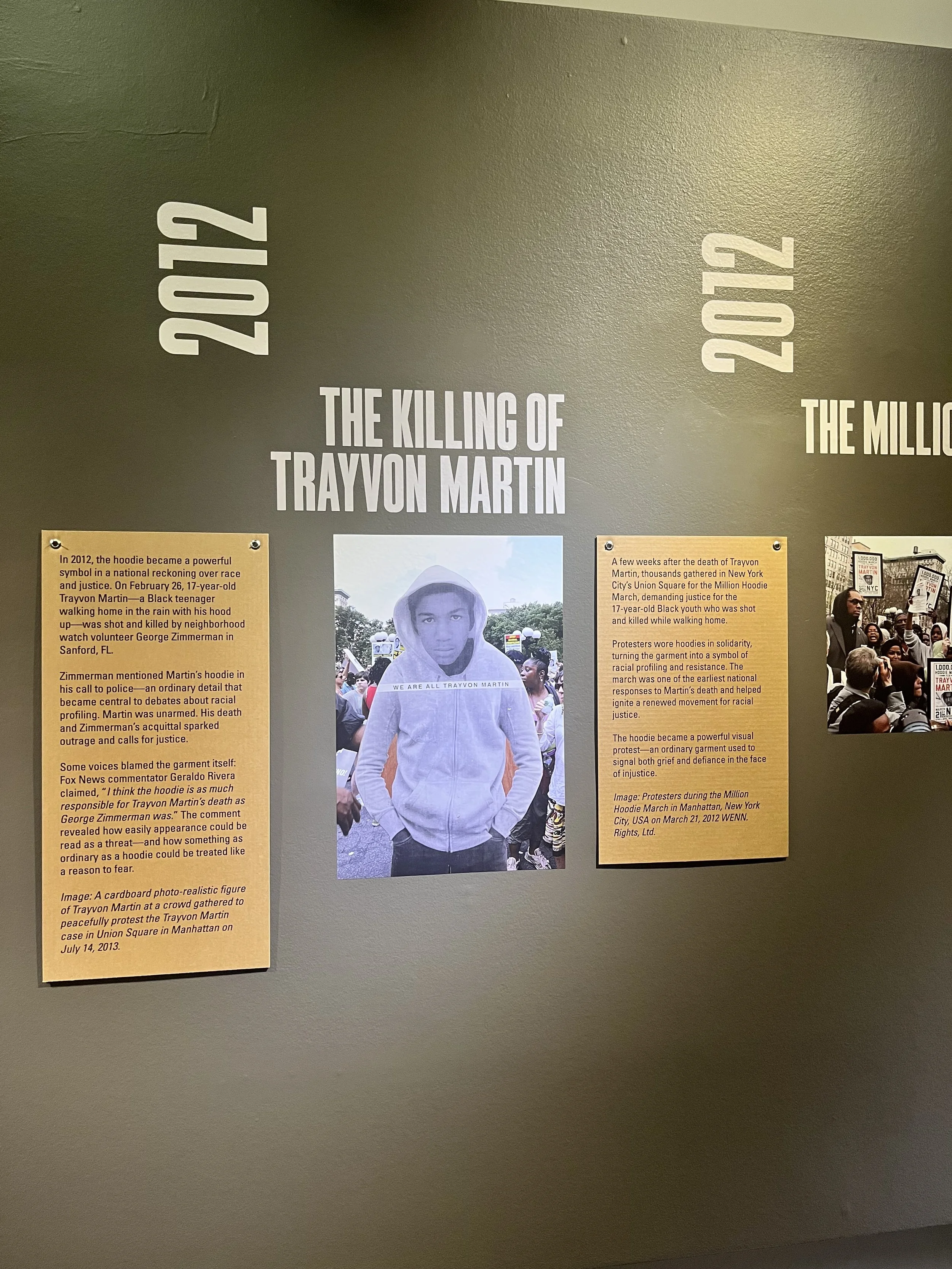

In recent years, the hoodie has been framed through a narrow lens, particularly in conversations about policing and racial profiling against Black individuals. The murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2012, whose hoodie was cited to police as a “suspicious” factor in his appearance, became a catalyst for national conversations about race, clothing, and criminalization.

As the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum and international protests followed, the hoodie came under even greater scrutiny as a symbol of how clothing can be weaponized through racist and discriminatory violence. Keeping this in mind, Bradley and Flusche resist flattening its meaning. Instead, they curate an exhibit that holds contradiction as a central theme.

Originally conceived and curated by Lou Stoppard as an exhibit at the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, the Atlanta iteration reimagines the hoodie through a regional lens. Bradley, whose work centers on Southern culture, was prepared for the challenge. “Figuring out how to place the hoodie as a marker of southernness in more recent memory was an intriguing and new challenge for me,” Bradley said. “The result is an exhibition that treats the hoodie as an artifact that reflects multiple truths depending on who wears it, where, and why.”

Photo by Tyra Douyon

Visitors move through sections about the garment’s influence on local Atlanta designers, its presence in superhero stories, and can participate in an interactive area to design their own hoodies. Towering over one of the rooms is the Hoodie Project, a sculpture by Billie Grace Lynn that reckons with the complexities of racial injustice in the United States.

Upon entering the space where the sculpture was, I was immediately intrigued by the forbidding and billowy figure but admittedly I was also fearful. The human figure that is meant to be imagined wearing the black hoodie is designed with a drooped downward glance with hands placed in the front pocket. As I observed the structure absorbing the small space around it and casting it in shadows, I started to imagine a dangerous person inside the structure.

Granted, it’s 26 feet high and mimics the shape of an invisible person, but it left me to question why I was so uncomfortable. Beyond the intrusive figure itself, I started to examine my own biases and the cultural narratives and negative stereotypes I’d absorbed over the years about hoodie-wearers and what can be perceived about them. Judging from the visitors around me, who were also quietly navigating the space while offering weary and introspective glances up at the sculpture, I wasn’t the only one enlightened by the complexity of the piece. That complexity sits at the heart of the entire showcase.

The hood has a role of both identity keeper and concealer. Someone’s identity can be misrepresented—even targeted—because of what they have on. The narrative shifts depending on who is wearing it.

Dr. Regina Bradley

“It was extremely important for us to layer the hoodie’s narrative because it symbolizes multiple truths at once: a garment intended for comfort but also capable of putting the wearer in an uncomfortable situation,” Bradley said. “The hood has a role of both identity keeper and concealer. Someone’s identity can be misrepresented—even targeted—because of what they have on. The narrative shifts depending on who is wearing it.”

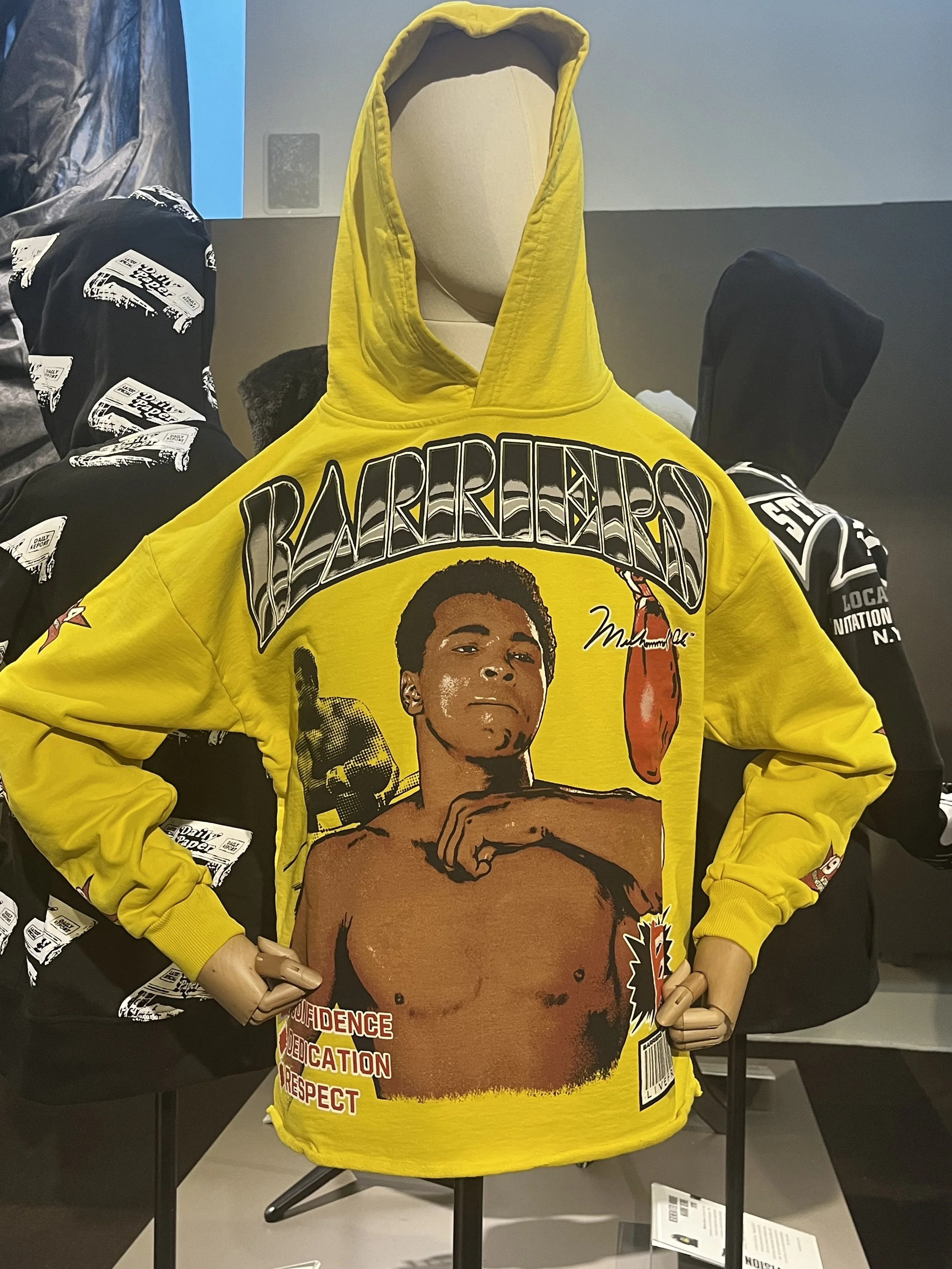

Design plays a critical role in communicating those narratives. During the research process, Bradley was especially drawn to how logos and materials such as cotton, silk, and polyester tell distinct stories and “suggest sophistication, leisure, authority, or even place.” A logo can function as a cultural shorthand, embedding various meanings into a garment. Together, these elements reveal how even subtle design choices shape how a hoodie and its wearer are understood by the world.

Several pieces in the exhibit capture this duality. One that stands out for Bradley is the anti-facial recognition hoodie from Anti-AI, which is designed to preserve anonymity in an age of surveillance. Its purpose to evade technology speaks directly to contemporary anxieties around visibility and control. Equally powerful for her is the “Trayvon” hoodie from the Trayvon Martin Foundation.

Photo by Tyra Douyon

On the front is a picture of Trayvon in the gray hoodie he wore the night he was fatally shot by George Zimmerman with the words “Trayvon Lives On” in bold red letters across the top and bottom. The garment holds grief, activism, race, and social media-driven political awareness in the same frame, underscoring how a single article of clothing can become a vessel for resistance.

Atlanta’s influence anchors the exhibition’s narrative arc. By spotlighting hoodies from local businesses like Eastside Golf, Grady Baby Company, and Kultured Misfits alongside global artists, celebrities, and even hoodies owned by MODA staff, the exhibit portrays Atlanta as a center of fashion innovation. “Atlanta is a long-standing incubator of creativity,” Dr. Bradley said. Fashion is often an understudied aspect of Atlanta’s creative expression, and we wanted to include local designers and entrepreneurs to demonstrate this side of Atlanta culture.”

That local focus extends into the exhibition’s engagement with Atlanta’s hip-hop culture and the hoodie’s function within it. The exhibit highlights these signature moments, including T.I.’s 2004 album cover for Urban Legend, where he appears in a grey hoodie and cocked hat and Ciara’s album cover for Goodies, featuring her signature pink hoodie that balances her femininity and tough exterior.

The exhibit also examines the Black LaRopa hoodie Gunna wore in his 2022 RICO arrest mugshot. The image circulated widely online fueling consumer demand for the hoodie and becoming a key part of Gunna’s branding. The exhibit plaque notes, “This moment shows how the hoodie continues to straddle contradictions: stigmatized in one setting, celebrated in another, and always central to hip hop identity.”

New to exhibition-making, Dr. Bradley approached the work as an exercise in storytelling through objects. Along the way, she made unexpected discoveries, including the existence of “Hoodie Horror” as a genre in films like Eden Lake (2008) and Cherry Tree Lane (2010), which highlight just how deeply the garment has penetrated popular culture.

This narrative is also showcased in the superhero stories across film and television from DC’s Green Arrow, Marvel’s Spiderman and Luke Cage, and HBO’s Watchmen series. As displayed in the exhibit, all the characters don a hoodie as a key part of their disguises to maintain their anonymity and appear unapproachable, but as they fight injustice in their cities seeing their hoodies becomes a symbol of safety and protection. This is a far cry from their initial placement in the audience’s consciousness as a dangerous object.

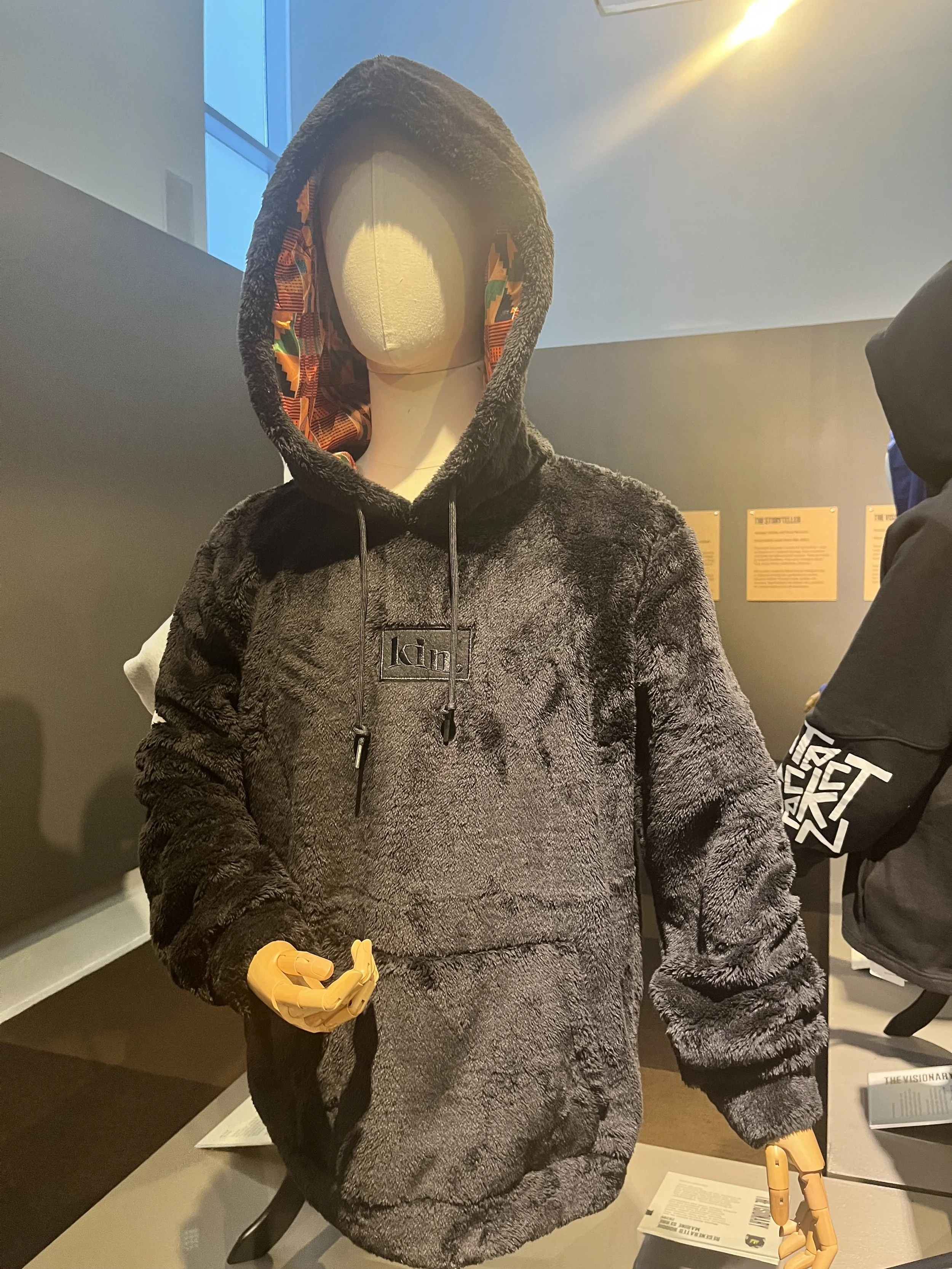

Ultimately, The Hoodie: Identity, Power, Protest MODA exhibit resists definitive answers. Instead, it invites inquiry. I was left wondering about the deep cultural significance of fashion and how it shapes our understanding of each other. I realized from locker rooms and classrooms to horror films and hometown heroes, hoodies continue to evolve, their meaning unmitigated and still always open to interpretation. My research came to life in ways I didn’t expect beyond this piece because of the visibility they received from this MODA exhibit. I bought a hoodie from Kin Apparel, a Black woman-owned company that offers satin-lined apparel. And I plan to purchase hoodies for children I know from Sense-ational You, a sensory-friendly clothing line for individuals with unique sensory needs, including autistic children and adults.

Overall, Bradley hopes visitors leave the exhibit with new questions about the hoodie’s popularity and power, and perhaps a renewed curiosity that extends beyond the museum walls. “Ideally,” she says, “a visitor’s curiosity is piqued to the point they go off and do a little research of their own on how fashion, power, and identity intermingle not only in the South but in American society at large.”