[[bpstrwcotob]]

Shutdown.log

if (soul == None): / log("disconnection detected"); / backup("last known version of me");

if (soul == None):

log("disconnection detected");

backup("last known version of me");

if (heartbeat.variation < 0.01):

run("old songs");

try:

trigger("feeling");

except:

pass

if (voice == empty):

load("your messages.txt");

loop:

hear("you saying goodbye");

if (system == unstable):

restart();

load("quiet");

if (presence == ghost):

print("I loved you");

shutdown("gently");

Instructions for leaving.

When there’s no one left.

Parietal Operculum

Someone said your skin / is like velvet, which produced only a worn out / glimmer in the region, but when I touched // you I was myself full of ocean nettles, scalpels / and scythe, yellow and deep rose, forest green.

We're proud to feature this poem from Kristyn Snedden’s chapbook Urchin to My Shell, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist of The Headlight Review’s 2025 Poetry Chapbook Contest.

Lessons from my husband’s neurologist

I listened while he unfolded every millimeter

of the cortex that cuddles up to the insula,

all that integration. His voice was driftwood

full of holes and swirls. Simon Lacey says the parietal

operculum is where we sense texture through touch,

even if all we do is read it somewhere, our brains

light up on the machine. Someone said your skin

is like velvet, which produced only a worn out

glimmer in the region, but when I touched

you I was myself full of ocean nettles, scalpels

and scythe, yellow and deep rose, forest green.

I was a wilderness captured by the dune,

waves ran over me in the sea of you

and no thought lingered, just the colors

and touch of mossy dark, the taste of brine.

Adrift in that damp sea, that gentle tide,

every minute as sweet as the sting

of the Atalla jellyfish, as bright as a supernova.

Ars Poetica with Amateur Tarot

While my lover the tarot reader is comatose / in the bedroom after a night of talking to a god / I could not taste or touch, I scatter / the cards across the living / room like spores

into darkness.

We’re proud to feature this poem from M. Ezra Zhang’s chapbook Self-Portrait with LSD and Mirror, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist of The Headlight Review’s 2025 Poetry Chapbook Contest.

While my lover the tarot reader is comatose

in the bedroom after a night of talking to a god

I could not taste or touch, I scatter

the cards across the living

room like spores

into darkness. Yesterday

under the domination of that god, my face

thrummed in my hands as if

I were wielding a bucket of light. Recoiling from its glare

I was disgusted to find that it followed

me everywhere.

Knowing nothing

about divination I pull three cards:

the moon, the tower, the devil.

If you, like me, don’t know the interior of these

cards, I beg you not to look for them.

It will only make things worse. Look at me

instead while I tell you something true:

One night you are moving

under the hot wet animal of the moon.

You coil upwards a couple hundred

spells until the horizon drowns into the earth

and abandons. At the eye of the tower you become the

eye of the tower. The black grass from below

swells heavenward and then you

become that darkness too.

Today on earth, the living

room window transfixes me

for hours but I find no tranquility in the scene

of the people of the world arriving

at where they need to be.

an “i want” poem about hilarious masochism

to get sunburnt / on the scalp & the top of the shoulders / where it freckles after the second burn

to get sunburnt

on the scalp & the top of the shoulders

where it freckles after the second burn

& that sun burns the sand too & it grinds between heel & flip flop

until, sandals abandoned, cold salt waves engulf ankles & up

to miss the step

the one to the garage & shins collide with wooden doorframe

dad curses, shit, you startled me, stop running

so damn fast through the yard

& for some reason it’s funny to feel the cool cement of the garage against

those knobby knocking skinny knees

& each bruise evidence excitement & dad

cared enough to cuss

to crash the bike

milli—micro—nano seconds before it hits annie & both challenger & chicken

fall into the grass bruising on dirt

blushing under sun & adrenaline & full-stop stupid

& the bike hits the telephone pole before it cruises into the street

& two girls now have grass stains up their (one pale, one olive) forearms slight

& bug-bitten & tree bark-carved

& everything is laughing, the summer, the sun, the breeze,

& annie gets the bike & starts up the hill for her turn to come down again

to crawl back in the window

dictionary under armpit & shingle pieces breaking palm skin

soft landing on the twin bed where the cat tilts his head

at crickets under the sill

& the ribs have burned & burned from summer’s insufferable

way of causing laughter

& the sun is pulling its linen blanket over its head now

& the power is still out & the Nintendo DS died two

hours ago & the bookmark sits at R

in the dictionary: raucous, rabid,

rampart, rapeseed,

& being bored is worse than bruising or burning

because it leaves the fewest marks

Are You the One?

My first marriage ceremony was held in my mother’s apartment on 79th Street just east of Park Avenue in a pre-World War Two building with a doorman and canopy.

It was just before Christmas and the loop of carols played over the loudspeaker in the Mobile, Alabama airport. I had spent the day landing a client. My cheeks hurt from the smile I wore sitting across from him, side-eyeing the Auburn University Tigers football helmet, which served as the base for his desk lamp. My client’s office was decorated with photographs of him shaking hands with politicians including then President Jimmy Carter. On the wall was his university diploma, class of 1959. Doing the math, he was about ten years older than me. At thirty, I was a senior vice president of the mortgage banking firm I worked for. Seven years of hard labor traveling around the country over holidays and long weekends.

I listened attentively as my client shared his financial problems and addressed each one of them. And then I made the ask and waited. Silence. I glanced at my watch hoping that I wouldn’t miss my connecting flight. Bingo.

He leaned across his desk and shook my hand longer than was necessary. “We have a deal, Little Lady.”

I imagined myself picking up that lamp and throwing it at him for calling me “Little Lady.” I was hardly a Little Lady, standing 5 foot 7 inches in my bare feet. I thanked him for the confidence he had placed in us and told him I’d send a letter of engagement as soon as I was back in my office in Boston.

“I’ll look forward to hearing from you,” he said and shook my hand a moment longer than necessary. Was he flirting with me or was that just my imagination? He was hardly my type with his stomach hanging over his belt, his hair slicked back with too much pomade, and the cigar he pulled on during our meeting. He was much too old for me and geographically undesirable.

Why do unattractive men think every woman is fair game?

I should have been happy that my sales trip was a success, but I had done this one too many times. I missed my toddler son. I was tired of flying around the country, and I was still recovering from a messy divorce. Are there any other kinds (other than Gwyneth Paltrow style conscious uncouplings)? I often thought about quitting, but I needed the income. My ex couldn’t or wouldn’t pay me alimony, so it was up to me to keep a roof over our heads.

The Mobile airport was filled with passersby carrying shopping bags rushing to their gates to board flights or greet disembarking passengers. Men smiled at me as I walked through the terminal. Swinging my briefcase, I must have looked out of place, a “Little Lady” in a gray and white lynx fur coat.

I confirmed my reservation, filled out my company flight coupon, and gave it to the Eastern Airlines gate attendant. The short flight from Mobile to Atlanta was uneventful. We landed on time. I looked out the window as I climbed up the ramp; snowflakes were falling dusting the runways. I had never heard that there was snow in Atlanta. Waiting for my connecting flight to Boston, I settled into a seat in the Red Carpet lounge for frequent flyers of Eastern Airlines. Someone sat down in the empty seat next to me. I was reading a novel, or maybe it was TIME magazine. I was anxious to get home. The stranger addressed me, “Why is a stylish woman like you wearing a Mickey Mouse watch?” I looked up. The answer was that I had taken my son to Disneyland a few weeks earlier and wanted a souvenir.

While the announcement over the loudspeaker notified us of one delay after another with the snowstorm building in intensity, Stan introduced himself. He was a business consultant and had just had a meeting with the CEO of Coca-Cola. With thick brown hair and glasses, he stood 6’7” and was a smooth talker. He made me nervous, but I managed to hold my own telling him about the reason I was in the Atlanta airport. “I’m trying to get back to Boston, but it doesn’t look good.”

“I’m from Boston—Brookline, actually.” The street he lived on was three blocks from my house.

Stan asked, “If we get stuck here overnight, you want to stay at the same hotel? Separate rooms, of course.”

All flights up and down the eastern seaboard were cancelled. We had dinner paid for by Eastern Airlines and then walked around the Omni Hotel. It looked like a huge Tonka toy with an indoor ice-skating rink where skaters wobbled about and one or two feet as they practiced their figure eights and spins to organ grinder music.

“I love to skate,” I told him. “When I was growing up in Harrison, New York, my dad used to take us to an indoor rink, and when it was really cold, we went to one of the frozen ponds in our neighborhood at night. My sister and I took turns skating with my dad, and he loved to whistle as he glided around the pond. He was a good, all-around athlete. He taught me how to ski and play tennis.” Too much information? I looked at Stan, wondering if I was boring him.

“Sounds like you had a pretty nice childhood. I grew up in the Bronx. By the time I was sixteen, I was nearly the height I am today. Everyone thought I’d be a basketball player, but it was hard on my back. I swim. It’s good therapy for the mind and the body. There was an indoor roller-skating rink near our apartment where the gangs hung out. That was pretty much it.”

He added, “Different sides of the tracks, but things even out in the long run.” And then he surprised me with a strain from “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off.” His soft baritone sounded rich and warm.

“One of my favorite Gershwin tunes,” he said. “Do you know it?”

I nodded. And he sings too, I thought.

We said our goodnights. At eleven p.m. the telephone rang. It was Stan. “What are you doing?”

“Trying to sleep.”

“Want me to come to your room? I can sing you a lullaby or whistle.”

“No thanks. I’ll see you in the morning.”

There would have been worse things than having him wrap his arms around me. This time I didn’t judge a man for trying, but this was too aggressive. Years later he told me had I said “yes” that would have sealed the deal—a woman who took chances.

~

Seated next to one another on the plane (he had rearranged our seats), we were holding hands and the electricity between us was palpable. I stared at him while he had his nose in a book: deep brown eyes, perfect smooth skin, thick dark brown hair that was unlikely to fall out in old age, a trimmed mustache, and pillowy lower lip. He was dressed in a business suit—striped tie, starch white shirt, and navy-blue pants and jacket. He looked uncomfortable in his seat, which didn’t accommodate his tall frame. I was curious to know if all of him matched his height. I shivered. I turned away when he looked at my long reddish-brown hair, fair skin, hazel eyes, and Diane von Furstenberg wrap dress.

“Are you cold? I can adjust the air.”

“It’s not the air.”

He smiled and went back to reading.

We shared a cab from the airport to Brookline. Stan asked for my telephone number and gave me his. “Feel free to call me in case I don’t get back to you soon enough.” He leaned over and kissed me on the cheek. We didn’t mention his offer to come to my hotel room. Maybe we’d get to know one another well enough to talk about it.

I unlocked the front door, tiptoed up the stairs, and kissed Josh goodnight. He didn’t stir. I ripped off my clothes and fell into bed.

The next few days the snow continued falling. Public transportation was shut down into Boston. People with skis shushed along the Metro tracks, and old ladies slipped on the ice that built up in front of grocery stores and pharmacies. Power had been cut off. We relied upon our two fireplaces to keep the house warm. Fortunately, we had a stack of dry chopped wood. My mother-in-law was with us and took charge of my son Josh while I caught up on work at home. The postal service was still operating. I typed up a letter of engagement, read it over the phone to my boss, and then sent it off to our client in Mobile.

I waited for Stan to call. When the telephone rang, I was excited and relieved to hear his voice. I admitted that he had tried my patience.

“I’ve thrown my back out,” he said. “Would you mind coming over with some food? And I’d love to see you, but I’m not at my best.” I bundled up against the frigid air and carried a generous package to his apartment. I found him lying on the floor groaning in pain. “What happened?” I asked.

“It’s not easy navigating a world made for people shorter than me—which is mostly everyone. I leaned over my bathroom counter just to shave, and I felt a nasty twinge. The doctor told me to lie down on the floor, take some aspirin, and wait for the pain to pass. He forgot to say that I needed the company of a beautiful woman.”

I blushed. Somehow, in spite of his handicap, we spent the next hour kissing. Nothing like the parchment pecks that my ex-husband begrudging planted on my cheek. His hands were strong and assured—there was nothing tentative about him. Was this the man I had been looking for? Was Stan the reward for having endured a passionless seven-year marriage?

“Could you get me a glass of water?”

“Anything else before I go? My mother-in-law is staying with us. I don’t want her worrying.”

I stood up, put my sweater on, and buttoned my jeans. He grabbed my hand and pulled me back.

“Wait a minute Mister. I’ll be back, I promise.” He looked so helpless. “I hope the next time I see you, you’ll be standing up. This isn’t a good look.”

Stan laughed. “Don’t I know it? Just let yourself out. I can’t stand up or I’d walk you to the door.”

I slid home over the snow boots barely careening into other pedestrians out at ten o’clock in the evening. My body was on fire. I didn’t feel the cold and took off my scarf to let the air dry my neck. When I got home, everyone was asleep. I kissed Josh, tucked the covers around him, and turned off his nightlight, the stars vanishing from the ceiling. I was so happy I wanted to sing. I whispered, “Lullaby and Goodnight,” although he didn’t hear me.

I ran a bath and soaked in the warm water; it would have been easy to close my eyes and drift off. Instead, I toweled off and got into bed, pulled into a deep dreamless sleep. The next morning the sun poured into my bedroom window, and I heard the drip of icicles melting. I wondered if this was it—the storm had blown through, and we’d soon have electricity and heat. Josh crawled into bed with me, his hands gently caressing my face while he murmured, “Mama, Mama.” The sweetest sound. I curled my body around him.

I wasn’t looking forward to going back to work as soon as the streets were cleared of snow and the MTA was operating.

Stan and I became exclusive, dinners at quaint Cambridge restaurants, double dates with his best friend Howard Schwartz and his wife Jackie, art exhibits, and movies. One stands out—My Brilliant Career. Set in Australia, the film features a spunky young woman who plays tricks and dreams of becoming a writer. She questions the intentions of a wealthy landowner who proposes marriage.

“What did you think of the movie?” asked Stan preempting me.

“I can identify with the heroine’s feistiness, her passion to become a writer.” I stifled a sigh not wanting to seem a victim. “But right now I have bills to pay.”

He pressed me. “What do you think of her decision to reject her lover’s marriage proposal?”

“You first.”

Stan adjusted his glasses, which I had learned was his habit when he wanted to buy himself some time to think. “I guess every woman needs to choose her own path, but I think she could have had both. I don’t understand why she questioned his love.”

“Maybe she thought she didn’t deserve it.”

“I think she misinterpreted his intentions. I think he was in love.” As if ending the discussion, he leaned over and kissed me. Unlike the heroine, I felt in that moment that I deserved him—all of him.

Initially we had no intention of bringing our children together. It was much too soon for that happy “blended family.” Instead, we kept our romance under wraps.

~

Stan made reservations at the Castle Hill Inn in Newport, Rhode Island for our first weekend away. What to wear? I chose a pink cashmere turtleneck, and pastel, paisley skirt with beige suede boots for the two-hour drive and packed two different outfits—one for dinner and the other for a walk on the beach.

“How do you know about this place?”

He was evasive. “I’ve been there.” I was curious to know if it was with another woman, or if he had taken off for a break after his divorce. I didn’t know much about his ex-wife, and I was glad. I would have had to share things about my ex, and the stories weren’t very flattering to me or to him.

Stan turned on the car radio; the classical music filled the comfortable silence between us.

The windows of our suite overlooked Narragansett Bay, and there was a claw foot tub, a nod to the inn’s beginnings in the late 1800s when grandees summered there. We didn’t bother unpacking and instead slid under the sheets. Stan was a masterful lover, one minute gentle and the next insistent. I discovered what his mustache was for. It sent shivers down my spine. Three hours later we showered, dressed, and went out to dinner at the White Horse Tavern in a red clapboard house. The main dining room was lit by candles in keeping with its seventeenth-century vintage. Stan ordered a dozen oysters. We were ravenous.

“What kind of wine do you like?’” he asked.

“I’m going to have the cod. What about a Pouilly Fuisse?”

“Let’s splurge. Why don’t we have a bottle of Pierre Jouet?”

“Are we celebrating something?”

The flame of the candles on the table lit up his face. “Every minute alone with you is reason enough to celebrate.” Bring it on.

I tipped an oyster and juice into my mouth. It was fresh and delicious.

The waiter came over to take our order. When he left, Stan asked, “Do you like to cook?”

“Chocolate souffle, Moroccan chicken, turkey with chestnut stuffing and sweet potato pudding, pot roast and latkes. Anything really, so long as I have a good recipe and can buy the ingredients.”

Stan ran his tongue across his mustache to catch the oyster juice. “I’m moving to a house in a few weeks. It’s right in our neighborhood. You’ll have to christen the kitchen, and I’ll do the dishes.”

I took a sip of champagne and nodded. Did he see a future for us? I didn’t want to jump to any conclusions. I didn’t stop to think if he was right for me. I was being led by my beating heart, and not my head.

The next morning, we walked along the beach. Stan had a tape recorder and played Bach as the waves pounded the rocks along the shore. He pulled out a camera. “You look stunning in that heavy blue sweater. Let me take a picture.”

“Only if you let me take one of you.”

I let the wind blow my hair, partially hiding my face and then we switched positions. Looking at Stan through the lens, I had trouble catching all of him. I had to keep walking backwards. “Careful you don’t trip and fall.”

~

Our next outing was to his cabin in Quechee Lake, New Hampshire. He warned me that the amenities were basic. We decided to bring his sons who were six and eight.

“Why don’t you bring Josh? He’ll have fun with the boys.”

His confidence was catching, so I agreed. Since we were moving in the direction of becoming a couple I decided to give it a try. The evening before I made a lasagna casserole and Josh helped me with the crocodile cake—green food coloring mixed into the cream cheese icing, corn candy for teeth, M&M’s for the eyes and a tail that wound back on itself and into its mouth.

“What do you think, Josh?”

“It’s scary.”

“Maybe but it won’t bite you, I promise, and it’s going to taste delicious.” I swiped my finger through the icing bowl and offered it to Josh.

“Yummy.”

“I promised.”

“Tomorrow we are going with my friend Stan and his boys to their cabin in Quechee Lake.” I editorialized hoping that he’d be excited. Instead, he looked at me with his chocolate brown eyes, puddling with tears, and said, “No, I don’t want to go.” And then he had a full out cry. I held him in my arms.

“Would you like to sleep in my bed just for tonight.”

He managed a silent nod. I wondered if I was rushing headlong into one imaginary, big happy family.

Stan picked us up in his 1967 brown Pontiac. Half-hearted introductions. Apparently, his sons, Ricky and Noah, were in the middle of an argument and didn’t want to be interrupted by his father’s girlfriend and her son. We didn’t say much on the ride to the cabin, which was exactly as advertised—basic—it’s saving grace was the spectacular view of the partially frozen lake.

“Everyone up for a vigorous hike around the lake?”

I put on my boots and dug Josh’s out of his suitcase. Stan was already wearing his, as were the boys. This must have been a ritual. One shouted, “To the top.” The other groaned. “I’m tired. Let’s go half-way.”

“All right. Half-way it is. Probably make it easier on Josh,” said Stan. Then he added, “But Loren is an experienced hiker. She’d probably get to the top without breaking a sweat.” I gave him the side eye. Was he mixing me up with a former girlfriend, his ex-wife, or was he trying to sell me to his sons? Up to this point the only athletic sport we indulged in was in the bedroom.

The trees were covered with a dusting of snow, and the March wind stung. I tied a scarf around my face and turned the collar up on Josh’s snow suit. Stan took long strides dodging the snowballs his sons threw at him. Stan seemed impatient that Josh was holding us back. I kept asking him to slow down, but he just wanted to give his boys a vigorous outing, so Josh and I lagged behind. I consoled myself by thinking that Josh would be exhausted and not mind sleeping alone in a sleeping bag in the living room. There were only two bedrooms, and the boys claimed the second bedroom without inviting Josh to join them. It was apparent they didn’t want anything to do with a five-year-old.

When we got back to the cabin, I put dinner together and the boys were directed to set the table. They groaned. “Dad, fork on right, spoon on left?”

“What do you think?”

“Fooled you,” said the older boy, Rick. The three of them laughed. I didn’t get the joke. This must have been another one of their rituals.

Even Josh scarfed down the lasagna. I brought out the crocodile cake. It was a big hit, well worth the effort we had made. Stan declared it a masterpiece. I was thrilled.

“Why don’t you play a board game with the boys? I’ll do the dishes.”

“I don’t mind that arrangement at all.” Stan gently touched my neck and whispered, “And after they go to bed, we’ll play our own game…”

The boys chose Chutes and Ladders. I let them win. Josh found a corner and turned the pages of Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, telling himself the story. Rick said, “He’s got it all wrong.” I told him that Josh didn’t read yet. “Would you like to read it to him?”

“Forget it.”

Lights out. The only sound in the cabin was light breathing. Outside, the sounds of the ice cracking echoed through the woods. “Do you think this was a good idea?” I asked Stan. “Maybe we should have waited or done something together less ambitious than a weekend here.” If I had doubts, I should have voiced them sooner, but Stan sounded so enthusiastic that I went along with it.

“Sure. They needed to meet one another soon or later.” He then ran his finger from between my breasts and down my stomach to his intended destination. I gasped. He covered my mouth with his.

Breakfast was an assortment of cereals. The older boys got into an argument and started throwing corn flakes at one another. Stan laughed. I wasn’t amused. I thought he should discipline them, but as with many weekend fathers he didn’t put a stop to their game. The table was covered with cereal. I cleaned it up while Stan did the dishes.

We didn’t discuss the weekend, which I voted an epic fail, except for the crocodile cake. Instead, we resumed our routine of going out on dates on the weekends without the boys. Three years into our relationship, we closed all the blinds and danced naked to “Saturday Night Fever.” We spun around and ended up on the floor making love. It was the glue that held us together.

Our conversations were highbrow. He was obsessed with quantum physics, which was well beyond what I could understand, but I’d nod and ask appropriate questions as if I knew what he was talking about. “Quantum physics operates on the atomic and subatomic level.” Huh? I did better with his lectures to me about “corporate culture,” a concept he made popular with a colleague at Harvard University.

“Why did you go into this field?” I asked, struggling to understand how his mind worked.

“When I got my masters in anthropology, I could have done research on indigenous tribes or family relationships. But there’s no money in that. I decided that studying corporations was the way to go. It’s been very lucrative. I get $25,000 a speech. You’ll have to come with me one of these days.” I did, and afterwards we had sex in the back of the limousine on the client’s dime.

~

I was Stan’s plus one at a dinner party in the suburbs given by his associate, Jim Bailey, president of Cambridge Associates. “You’ll enjoy it,” he said. “Good food, good wine, and good company.”

“Who’s going to be there?” He explained that the guest list included Howard Schwartz and Jackie; Warren Benis, a professor in the business school at USC, who was in town for a conference; and Werner Erhard, the founder of est Training, and his wife Hannukah. “I sit on their board. The company is going through growing pains and Werner asked me to help him reorganize.”

“est—I didn’t know you were involved with it.”

“Yes, you might want take one of their seminars.”

I got defensive, “Do I need fixing?” He assured me that was not what he meant. “The skills they teach are beneficial for everyone. Even me.”

“So I might gain more insight into the way you think.” Silence.

The dinner party was as advertised. Howard sat across from me. He kept staring at me. Was it my white angora sweater and pearl necklace or something else? I excused myself and went to the bathroom. Howard surprised me. “I need to speak with you.”

“Sounds serious.”

“I can’t believe I’m saying this. I am in love with you, totally and completely. I wish you had met me before you met Stan. He can be a hound dog. I don’t think he’s good for you.”

I was stunned. “Thanks, but I think I can take care of myself.”

Stan said he saw Howard following me. “What did he want? Did he hit on you?”

“No. He just wanted to catch up. See how you and I are doing.”

“You told him we are doing great, didn’t you?”

I nodded.

~

I was blind to Stan’s faults and ignored Howard’s warning. I was impressed with his accomplishments and addicted to the sex. I didn’t know where our relationship was going. I decided to explore job opportunities in Los Angeles so that Josh could be near his father—he wasn’t a good father but he was the only one Josh had, and I hoped that over time he would become more engaged with him as Josh got older. He was too busy building his career to give much thought to the son he had left behind. Ever the optimist, I interviewed a few firms and was made an offer to start work by June 1980.

I told Stan and gave him the chance to ask me to marry him, but he said, “I’m not going to tell you what to do. You have to make up your own mind.” It’s not what I wanted to hear. I wanted him to tell me that he couldn’t live without me, that I was the one. Instead, he accepted my decision once I accepted the best offer. He assured me that he’d visit me in Los Angeles. A year of bi-coastal trips later it was over. He had met another woman in Brookline with three children about the same ages as his two sons. Howard told me she was seven years older than he was, an interior designer, and an excellent cook. I forced a laugh, “He needs help in both departments.”

Howard added, “He’s really a mama’s boy. With three kids, she’s had plenty of practice.”

I was shocked that he gave up on me so easily. I wanted him to say he couldn’t live without me, that I was the one. That I shouldn’t move to Los Angeles. That we would make a life together.

Instead, he accepted my decision. His breakup gift was a book by Carl Sagan, which he inscribed: To one of the great ladies of the Cosmos, With love and affection, Stan, November 1980.

Letter from the Editorial Director

I don’t know about you, but I’m sick to death of the artificial bullshit glutting our internet. I’m sick of scrolling past stilted videos of eerily fluid, cartoonish people in nauseating yellow lighting.

I don’t know about you, but I’m sick to death of the artificial bullshit glutting our internet. I’m sick of scrolling past stilted videos of eerily fluid, cartoonish people in nauseating yellow lighting. I’m tired of wading through generated images of Jesus made of fruit and vedge, American presidents dressed like comic book characters atop armored eagles, imposter flood refugees with pleading pigeon eyes, and bipedal hedgehogs scrambling eggs. But, above all, I’m revolted by the notion that we should get used to AI generated text because the chatbots are here to stay.

In a few short years, social media companies, AI startups, and their sycophantic boosters have transformed our most powerful communications technology into a desiccated wasteland of “content.” In this desert of abundance, as much as half of new content is generated by machines, and already automated bots make up more than half of all internet traffic. Increasingly, bots generate the content, post the content, and consume the content, completely cutting humans out of the loop.

All of this would be fine if it was confined to blogposts on Business Insider or LinkedIn profiles. But the crumbling of those “services” is only a symptom of what big tech wishes for us all: a human bot culture devoid of real feeling, of real connection, of real expression. Let, they say, the regurgitated average of all that has already been done or said be enough to say who we are, what we feel, how we love. We must reject this premise.

I’m not foolish enough to believe a new issue of The Headlight Review might herald revolutionary change. But let it be a salvo in the battle against the artificial, a barbaric yawp of human expression against the spinning fans of the datacenters that threaten to burn us up. And this howl’s a good one. We have powerful fiction edited by Mary McMyne, poetry edited by Abhijit Sarmah, and the largest collection of creative nonfiction we’ve ever published, including moving accounts of other institutions that have stifled us, love and family, and the timeless importance of literature. You’ll also find paintings, watercolors, and charcoal drawings. None of it, I’m proud to say, generated or assisted by AI.

This is our biggest issue yet, and I’m so proud of the work we’ve done to grow in these last two years. I’m also excited for the year ahead. Lately, we’ve been thinking a lot about THR’s place in our local community, and we’ve decided to use next year to consider our Southern roots. Volume 4 will be a special, double issue of the journal considering “New Southern Writing,” and I’m excited to get started on the work of connecting with nearby editors, writers, and artists to help showcase our region. We’ll have a lot of great regional content in our “High-Beams” section, too.

In the meantime, though, please enjoy this issue. We’ve worked hard to bring it together, and we hope you’ll agree it’s a testament to the supremacy of human expression at a time when that’s more threatened than it’s ever been before.

Holy Door

It was late August, not a tree or lick of shade to be seen; the sapping heat pulsed like a demon. We made our way in a straight line toward the recreation room, a dreary concrete block building, as if we, too, were prisoners.

“I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

—Matthew 25:36

Stay on the sidewalk, the signs commanded, and we—my mother, my brother, and I—did, not that we were tempted in the very least to stray onto parched grass peppered with fire ant beds and sticky beggar lice and sand spurs. Towers loomed overhead like barbed-wire lighthouses, guards with rifles at the ready, a reminder of an unfathomable life at Tomoka Correctional Institution, a maximum-security facility in Daytona Beach. It was late August, not a tree or lick of shade to be seen; the sapping heat pulsed like a demon. We made our way in a straight line toward the recreation room, a dreary concrete block building, as if we, too, were prisoners.

Earlier in the stark security offices, we exchanged our car keys and iPhones for radios the size of the earliest of mobile phones. In the center of the bulky black boxes was an emergency button, and we were to affix these radios to our waists, but already mine wouldn’t clip properly; the clasp was broken. I clutched it like a walkie-talkie instead. Up ahead, at the sidewalk’s end, a heavy iron door opened, and the smiling face of a tall man in faded blues appeared, and then disappeared. A few feet up the sidewalk later, the door opened again, and before it closed, I saw that the man’s expression was that of a giddy boy at Christmas. It was such an unlikely emotion, so strange in this doomed landscape. I looked up at the armed towers, nervous. Was such joy even permitted here?

The chaplain accompanying us opened the iron door, and we stepped inside to a standing ovation, over a hundred prisoners applauding. We were at Tomoka to honor my late father, a decades-long volunteer who established a Toastmasters chapter there and ran it every Thursday. He’d passed away a month before. Next to me, the hulking, smiling gentlemen who orchestrated this surprise greeting, introduced himself as Jonathon. My father had represented him at a previous, unsuccessful parole hearing. Dad had spoken of him frequently, of how he deserved to be released, and how certain he was of his redemption despite his crime (he never revealed why Jonathon was serving a life sentence). I had never understood that idea, that someone who had committed such atrocious acts could be redeemed. Plus, wasn’t punishment the goal?

As he spoke of Dad’s Thursday visits, Jonathon did not stop grinning. “Bob gave me his undivided attention. When other guys wanted to talk to him, I said, ‘Wait a minute, he’s here to see me!’”

He lifted a worn square of paper from his shirt pocket, the creases evident. It was a note my dad wrote after Jonathon’s first Toastmasters speech. Dad was a pharmacist, his early career in the family drug store in Monroeville, Alabama. He later became a pharmaceutical salesman in Jacksonville and was assigned to a territory that included the Tomoka facility. There was a need at the prison, he learned from staff and doctors. The “guys,” as my Dad always referred to them, wanted to be part of something, something more than what the prison offered. As Dad was an eloquent speaker, the kind of man you hoped made the toast at your wedding or the eulogy at your funeral, he was the perfect person to fill that void. He used Toastmasters to help the incarcerated men find their voices.

Jonathon didn’t unfold the note for us—the advice on that sliver of paper was his and his only—but knowing my dad, it was surely uplifting and encouraging, with a teeny bit of constructive criticism. And to Jonathon, it undoubtedly represented one thing: hope.

~

That was ten years ago. This year, 2025, is a Catholic Jubilee Year. Pope Francis announced that five holy doors in Rome would be opened, two of which he would personally oversee. These ornate doors are bricked up from the inside, and the breaking of the mortar symbolizes, like the ancient Jewish tradition Jubilee originates from, the release of prisoners, forgiveness of debts, and the restoration of harmony in the world. Catholics believe that all who enter pass through the presence of God. The first door was opened at St. Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Eve. The day after Christmas, a second was opened at Rebibbia New Complex Prison. Outside of the church community, this led to some headshaking. A prison? But Pope Francis, known for his outreach to city slums and AIDS victims, as well as for washing the feet of many prisoners, said, “I too, could be here.”

~

After the Memorial service, there was cake and coffee, and we were encouraged to mingle. The service had done a number on me. I wasn’t ready for mingling. I sat off to the side and focused on controlling my tears. A metal folding chair dragged behind me, and then a voice, “You got to stop that.”

I turned around to face a linebacker-sized man wearing mirrored sunglasses. Clearly he spent his allotted free time in the facility’s weight room. He lifted his shades to reveal red, swollen eyes. “Look at what you got me doing.” That made me laugh, and we talked and talked. “I loved your dad,” he said.

I thought that a splash of cold water on my face would help. Someone pointed me in the direction of the restroom, and I walked along the kitchen corridor by the leftover cake and coffee. At a counter, a man sorted through a stack of sketches. I recognized the artist’s style—a heavy crosshatch shading, a light stippling. One of his drawings—the regal head of a tiger—hung on the wall of my dad’s office. The man beamed with pride as he went through the sketches one-by-one. Faces with wide eyes, stern profiles, exotic animals, self-portraits. He selected an unfinished drawing, and deep in thought, leaned against the counter, and began a light crosshatching to make it complete.

I found the washroom and made myself as presentable as possible. The intensity of the day was enormous. If I could have walked out right then, I would have done so. But there were two men I still wanted to meet. Plus, I had no choice. This is an exaggerated comparison, but like the prisoners, I could not simply walk out just because I was tired and emotionally drained. I looked at myself, puffy eyes, head pounding. The cold water did not make me look any better. As I stepped out into the rec room, I was immediately stopped by a young man in his late twenties. “You read my story,” he said.

Years ago, Dad had given me a short story written in pencil on wide-ruled paper. I’d made notes in the margins and signed off with “Keep Writing.” The story was set in St. Augustine, where I live, and he had also lived as a teenager. It was a beautiful love story of a young girl who worked in a sweet shop—pralines, brownies, fudge—on St. George Street, the main pedestrian thoroughfare. As we chatted, I got the idea he wasn’t writing much anymore, so I encouraged him, noting that writing is hard work, and then I stopped myself. He knew hard work. Everything was hard here. What was I even talking about? Fortunately, he changed the subject, kindly asked what I was working on, but as I began, the iron door swung open, and a guard entered blowing a whistle. The room went silent, and without a word, every prisoner found a place, back against the concrete block. Each man was counted, another whistle was blown, and everyone went back—slowly—to what he’d been doing.

I noticed that the writer had positioned himself in the count line beside another young man. His friend looked so familiar—square jaw, dark eyes, a handsome face, a stocky build. I’d noticed him when we’d first arrived, and as the pair, heads together, went back for another round of cake, I strained to see the name on his breast pocket. I did know him, or knew of him. He was also from St. Augustine, and his face had been all over the news in the past few years. He’d been convicted of strangling his wife, leaving her on the beach, waves crashing over her. I watched him, now friends with the young writer; they had their heads together like teenage boys, laughing and palling around. I wondered if they had known each other in St. Augustine, or if their hometown had simply brought them together on the inside. They were like children joking and licking cake icing from their fingers. All around me there were small groups of men talking with my mom and brother, all like old friends or relatives. Collectively, in this room, there was an unbelievable past of horrific crimes and violence, yet there was happiness. Genuine happiness.

I asked around and finally found the two men I wanted to meet, dear friends of Dad’s—James and Jimmy. He spoke of them a lot, but as always, he never mentioned their crimes. Jimmy’s wife had passed away years ago, his grief causing the rage and crimes that had brought him to this place. He had a grown daughter on the outside, and grandchildren. I also knew that he had been very ill recently, but that day he wore an infectious smile. Jimmy was originally from Alabama, and a loyal Crimson Tide fan. My dad was an Auburn fan, and that heated collegiate rivalry had become the origin of their friendship. Jimmy had a folder in his hand, the kind you used in grade school to keep math separate from history, English from science. It was bright green and had been so well taken care of it looked brand new. “This is contraband. Anything you got in your cell,” he whispered. “They can take it away.” He offered the folder to me, as if he were an FBI agent. “Your dad gave me this.”

In the sleeve of the green folder was an orange and blue paper plate with the Auburn University logo. The table erupted in laughter. The week after Auburn beat Alabama in the Iron Bowl, Dad was there for the Toastmasters meeting. After speech practice, dessert was served, and Dad brought Jimmy a slice of pie on that plate. Jimmy thought it was the funniest thing. It was a long-running gag between the two of them, each trying to outdo the other, but clearly Dad won that time. Somehow Jimmy had managed to save the forbidden paper plate in his cell with that folder, passing it off as a document for years. Jimmy would later go on to be released earlier during COVID because of a cancer diagnosis. I often think of him sitting by his daughter’s screened-in pool, drinking coffee in the morning, free to enjoy it where and when he chose.

Though Dad also talked of James, it was more of his work on the inside, his yoga practice and meditation. I didn’t know much of his background or his family. He had severe blue eyes, a confident smile. As Jimmy and I talked SEC football, James had been mostly quiet. Now he looked around the room, and then back at me. “Is this what you thought it would be like?”

“No, it’s—” I said, struggling for the word. “Happier?”

He smiled and shrugged. “Well, in here, maybe. It’s not what it is out there.” He motioned toward the concrete block buildings that housed the dormitories. Some of the dorms could be violent and dangerous, he explained. The radio on my hip was uncomfortable and clumsy. Sometime during our conversation, I’d set it on the table. James motioned to it, and in a serious tone a reminder of where we truly were, said, “Better put that back on.”

“When you get home,” the chaplain told me as we were walking back down the sidewalk in a straight line, this time toward the security offices and the exit, “don’t search for these guys on the internet.” Of course, I would do exactly that. I fell down a rabbit hole at the state’s Department of Corrections site. I discovered their crimes—premeditated murder, armed robbery, assault with a deadly weapon—and then I stopped. I did not need to know the details of their crimes. There was no making sense of their past, no resolving who they were with the sympathy and kindness they had shown my family, and most of all, their respect and love for my dad.

~

On December 26, 2024, when Pope Francis arrived at the holy door of Rebibbia Prison, he stood from his wheelchair, took halted steps, and knocked on the ornate bronze door. It slowly opened, a gesture of easing open the doors of our hearts, and he passed inside. Despite its lack of beauty, I am reminded of that iron door at Tomoka, and the men behind it so many years ago, how they deserve what the pope refers to as an “anchor of hope.” I saw, if only for a few hours at Tomoka, how hope worked its magic—the look on Jonathon’s face, unencumbered by despair and loss, the creased note in his pocket, the Auburn paper plate in Jimmy’s green folder—all of this the outcome of those who have taken the time to bring hope to them.

~

When Michael was released, Dad was there when he walked out the prison door. He drove him to Jacksonville to a family member’s home, first stopping at Walmart where they shopped and purchased new clothes and supplies for Michael to get him started on a new life. Over the years, they had a regular lunch date and talked frequently.

The aneurysm that took my father’s life was not instantaneous. His brain was gone, but his body held on for days. He was a runner, a swimmer; his lungs were strong. He was simply not ready to go, therefore there was time for those who wanted to say goodbye. Michael was one of the first people my mother phoned. While he promised to come to the hospice facility, days went by, and we had not heard from him. One evening, just after sunset, there was a knock at the door. A black man, well over six-feet-tall with gold teeth and a worn leather Bible in his hands entered the room. He had an infectious smile. He came to the end of the bed, took my father’s feet in his hands. With the voice of a poet, he sang out, “My main man, my superman, my Hall of Fame.”

Three hours later, deep into the night, my dad slipped away quietly. I like to believe that Michael ushered him through that portal.

The Assembly Line Flow

Move and manufacture, / produce and progress / till guide, slide, shove / devolves to push, pull, / snap back on a fallen piece.

Steel slab after steel slab

guided, slid, shoved

into a push press

expected to deliver

on loose screws and bolts,

thirty seconds of ear-shattering bangs per sheet.

Bang!

Bang!

Eyes, mind closed to own smoke—

Overheat—

but maintain top speed.

Slow down, breathe—

become obsolete.

Move and manufacture,

produce and progress

till guide, slide, shove

devolves to push, pull,

snap back on a fallen piece.

Till each steel slab

on assembly line's flow

spawns a sob

masquerading as a rattled screech.

Bang!

Bang!

till screaming prayers to remain composed—

on shifts one through three—

looped on an endless repeat.

Rex

In the summer / we swiped at the sun / laughed until our sides hurt / Brave as kids could be

We're proud to feature this poem from Van G. Garrett’s chapbook Chinaberry Constellations: Odes, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist of The Headlight Review’s 2025 Poetry Chapbook Contest.

Big Mama’s house was two floors

of adventure:

A library of memories

A storehouse of stories

A patchwork of possibilities

Walls with hidden treasure

Creaking steps

A haunted attic

Photos and old records

In the summer

we swiped at the sun

laughed until our sides hurt

Brave as kids could be

Except for when we hard-sprinted

from a German Shepherd

with amber-colored eyes

named after a dinosaur

ACCESS_DENIED: heart.exe

Emotional drive: / fragmented.

> Running diagnostics...

Emotional drive:

fragmented.

Accessing main directory:

/hope/memory/you

Status:

file: touch.exe — missing

file: laugh.wav — corrupted

file: promise.txt — overwritten

folder: trust/ — access denied

Attempting repair...

Error: permission denied.

System prompt:

“Feeling requires vulnerability. Proceed?”

User input:

...

Suggested action:

abort.

Some systems forget

how to open again.

On the Death of a Queen

there is laughter like the ripples / when something dark breaks the water, / the laughter of children colliding

with the inert thigh of their mother / stood hollering

there is laughter like the ripples

when something dark breaks the water,

the laughter of children colliding

with the inert thigh of their mother

stood hollering,

there is the laughter of that discovery

of looking up at the mother’s face softening

and learning fear is a thing

you grow into

not out of,

there is the laughter of wind filling a sail

and two lovers’ hands on the tiller,

peacocks pluming and the dogs’ mistress returning

to a forest of tails around the hearse,

there is

the laughter of doors opened slowly by lovers

with a bottle in one hand and a lie in the other,

then the dark laughter of the same door closing some hours later,

the laughter of disbelief and crumbs in the bed,

there is

the laughter of the town crier drunk in the night

swaying under a lit window

where

the pert whisper of a curtain being drawn

seems louder than the tolling bells.

Scooch

The lower I scooch, the better the reception. / Like the signal’s intensity is what it is except / around me.

The lower I scooch, the better the reception.

Like the signal’s intensity is what it is except

around me. We’re watching The Rockford Files

in my father-in-law’s recreational vehicle in a

private drive in Ft. Lauderdale, James Garner /

Jim Rockford handing out uber-macho lectures.

It’s 1980. I’m a new dad and reading Faulkner

for a class. I catch the politics of calling women

Honey. The woman in tennis whites has framed

Rockford for felony murder. Her navel, an innie,

packs loads of social import before its vanishing.

Arthur Dixon, my kind father-in-law, stands. He

steps to the antenna. Now he’s motioning Scooch,

Jim Rockford smart-mouthing his way to triumph,

the rest of our family inside the house or at church.

This evening, Arthur loves his battery-powered TV,

asks if I like Florida. I say, Positively, as Rockford

calls up William Faulkner in a ’74 Firebird Esprit,

skillfully spinning a steering wheel—like America

is okay just fine but you need to be willing to, well,

scooch down so you catch sight of the road ahead.

Two Paintings

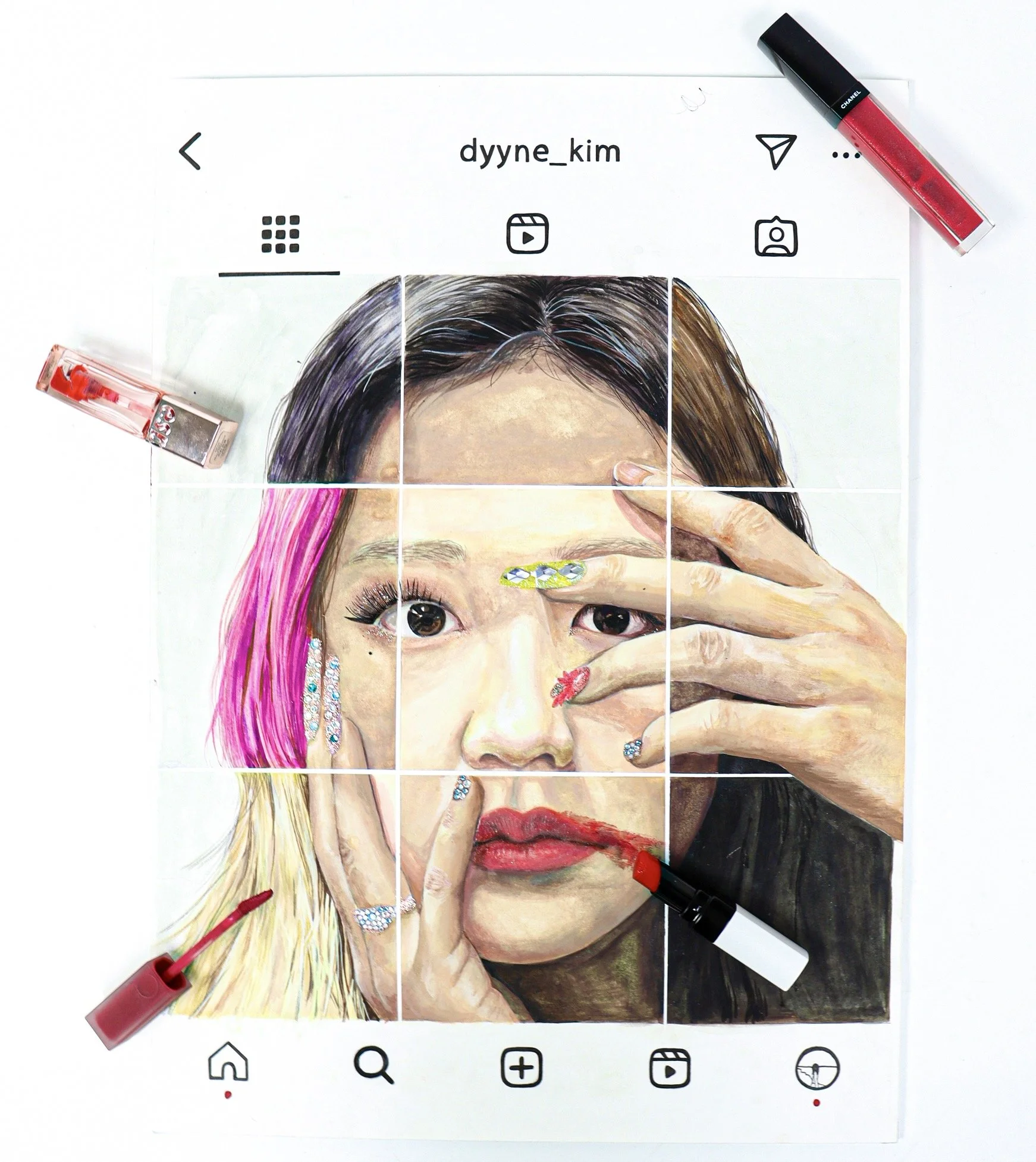

Artist’s Statement

Inspired by René Magritte and Daniel Arsham, I always present contrasting planes of existence in my paintings. To me, “dream” and “reality” are fluid constructs; our perception constantly shifts in response to what we see and feel. This ever-changing perspective is what draws me to art as it also serves as my bridge to empathy. While themes of inequality may not be immediately apparent in my work, they emerge through a hopeful lens, a belief that art has the power to transform how we see and engage with the world. By merging the extraordinary with the everyday, I aim to spark imagination and optimism. What may seem monochromatic to some is a vibrant color in the sky for others, and through my work, I hope to offer that sense of possibility—an invitation to escape negativity and see differently.

Pennypoker1919 to His Followers

Welcome to my playground sanctuary, friends/fans. This room is an extremely passionate and sensual place filled with mystery, desire, masculinity! I am permissive and open, live to be in front the webcam. Please play along and look at the bright side.

Welcome to my playground sanctuary, friends/fans. This room is an extremely passionate and sensual place filled with mystery, desire, masculinity! I am permissive and open, live to be in front the webcam. Please play along and look at the bright side.

My tip menu, dears:

Send me 1 token lol if you enjoy * 2 if you love * 10 for flash my stuff *

30 foreskin massage * 60 explain you my 53 seduction tattoo in ethereal detail *

70 intellectual conversation * 100 special armpit entertainment *

200 open window for view of downtown Kharkiv * 250 confirm theory that I look like

Timothée Chalamet * 500 virtually you sniff my bushy base * 1000 body tour *

1,500 we listen to the air-raid sirens * 3,000 I ship my underwear to your door anywhere *

4,000 seven somersaults in city rubble * 5,000 after the bombs, watch dawn over Kharkiv *

6,000 I introduce you to my hamster * 8,000 intellectual conversation plus *

10,000 become the god of my castle * 20,000 we meet in Kharkiv, you and I, for a night

of body contact only * 40,000 I take you around on my motorbike and you hold me where you

have need to * 50,000 real life body tour + armpit entertainment + bike tour + intellectual

conversation * 100,000 roommate life with you in your country after the war, you house and clothe and feed me and teach me the language and bathe me + unlimited intellectual

conversation + armpit entertainment + long tongue games + every orifice explored + 20 new tattoos *

500,000 I read to you what genre book or mystery you desire, I wash your feet and go for your shopping, we marry, you explore every orifice + intellectual conversation + Maserati convertible + I clean, do house jobs and fixing + unlimited foreskin massage, hundreds of handstands and somersaults

**************1,000,000!************** I belong to you, my every orifice for your curiosity and whim, even after my passing of twink years and you pass into aged years, I feed you, clothe you, bathe you, nurse you and wheel you, and when you’re disappeared I arrange all and inherit all and bring flowers, whichever you command, and keep the earwigs out of vase by your headstone as long as I am able and forever, my love.

Breakout

As soon as you reach a hand through them, / the walls will dissolve.

As soon as you reach a hand through them,

the walls will dissolve. Work with

the window there, above your eye-level.

Even if you have to stand on your toes

until your arches throb, become

a part of what you see through the bars:

the alley where snow hangs on in smears

under bare trees, garbage trucks

pack the sodden refuse, and a grey-striped cat

skirts the puddle under a downspout.

Your window will enlarge until it replaces

the entire wall, and you will walk out whole.

Memory of Exodus

may / these / bones / hold fast / to the / ticking before the / quitting

may / these / bones / hold fast / to the / ticking before the / quitting / we weren’t born a haunting / through numbing or rowdy melancholy / what we inherited meant to drown us / lungs ablaze we gripped / survival continuing as / prophetess spilling radiance / staving disaster determining fate / beyond an algorithm branch / few things are growing / faster from collapse / a dwarf star / uses its energy / before / imploding / our skin was / the night sky / containing / it

final sale: no returns

shelf life / expiration date / say you love me before the price tag peels off

shelf life

expiration date

say you love me before the price tag peels off

[aisle 13, fluorescence flickering—]

you reach for the last dented can of chickpeas & so do i & so we do

& suddenly our delicate hands are tangled like a broken barcode…

like an error in the quick scanner—like a misprint on the receipt of fate.

(does fate even issue refunds?)

the can rolls & gravity takes its tax—bottoms out—bottoms out—out. out. out. we both bend

down, the linoleum yawns. an abyss in the waxy white tiles. (buy one get one free. but

who is one and who is free?) a voice on the loudspeaker crackles: attention shoppers,

all prices are final. but my knees are on clearance—your laughter is marked

down—our shoulders gently brush & suddenly, the barcode of your

wrist is scanning my pulse. i’m full of expired metaphors. you’re

full of unspoken coupons.

(fine print: offers valid while supplies last)

the manager’s voice rustles overhead, a plastic bag in the wind. the fluorescent lights glitch.

the can rolls towards the underworld of the shelves. disappears. the lowest shelf. (where

forgotten things go. where we’re going. where we—) you giggle—you giggle—

you peel the last digit off a price tag and whisper it into my ear like a

prophecy. i mishear it as love. and then all markdowns,

we disappear in the bustling crowd.

(reduced for quick sale)

but then—

i wake up in aisle 13 again. again. again. the same can waiting. you reach. so do i. the scanner

beeps. the loop begins again. (does fate even offer exchanges?) the can rolls—but this time

it doesn’t stop. it keeps rolling, past the lowest shelf, past the waxed linoleum, past

the storeroom door left ajar. down. down into the supermarket catacombs

where carts with rusted wheels hum lullabies and lost items mutters

fainted names. (who is lost? the can? us?) you follow it. i

follow you. a door abruptly closes behind us. the

intercom gives a ding: attention shoppers,

this store is now closed.

and when we returned around—there is no aisle 13…13…13…

no fluorescent light—no way back. only shelves stacked

high with things we do not remember losing. And

shadowy price tags that bear our names.

this item is no longer available.

(final sale. no returns.)

On the 56th Anniversary of My Father’s Death

I decide to join the resistance against negativity. / To celebrate that cancer is a chronic illness now. / And that an old family friend will be able to live / with his blood cancer, stage four.

We’re proud to feature this poem from Elizabeth J. Coleman’s chapbook On a Saturday in the Anthropocene, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist in The Headlight Review’s Chapbook Contest in the Spring of 2025.

I decide to join the resistance against negativity.

To celebrate that cancer is a chronic illness now.

And that an old family friend will be able to live

with his blood cancer, stage four. In my mind,

I bestow on him the joy of knowing his sons’

spouses and children. Then, just as I do every day,

I empty our compost bin into our building's

larger one. Tuesdays the sanitation

department picks the compost up, and, after

a while, the resulting soil will go into New York

City’s parks, or so they say. The songbirds

are returning to Riverside Park, with their

capacity for human speech. My beautiful brown

dove is back, just four feet away, on my office

windowsill, watching me work.

Later we’ll head to Central Park, and, I hope,

come upon the saxophonist playing under

Graywacke Arch. My grandson

will skip over, put money in the case.

Last week, my freckled granddaughter

sold me a hand-painted bookmark

at her Ukraine fundraiser, with pink and blue

flowers, a sun, and a sky of paper white.

And today the woman who owns the frame store

between 95th and 96th on Broadway told me

she wants to go to outer space, as she smiled

from behind the counter in her little shop.

I pictured her en route in her white top,

leopard print leggings and black flats.

Love Song Intended to Stave Off Discontinuation of Relations (Unsuccessful)

I’ll be your boy toy!

Say you want me

And I’ll be your boy toy

If you want me hard to get

I’ll be your coy boy toy

If you want me Scottish

I’ll be your Rob Roy boy toy

If you want me to swell and sway with the crowd

I’ll be your hoi polloi boy toy

If you want me strong like copper and steel

I’ll be your smelted alloy boy toy

If you’re Jewish and I’m not

I’ll be your goy boy toy

If you want me saucy like Szechuan beef

I’ll be your Kikkoman-smothered bok choy boy toy

If you want me After the Thin Man

I’ll be your William Powell and Myrna Loy boy toy

Or, if you want something that melts in your mouth

Slavic and sweet (and you don’t mind

sharing the bed with crumbs)

I’ll be your Bolshoi Ballet/Chips Ahoy! boy toy