[[bpstrwcotob]]

Holy Door

It was late August, not a tree or lick of shade to be seen; the sapping heat pulsed like a demon. We made our way in a straight line toward the recreation room, a dreary concrete block building, as if we, too, were prisoners.

“I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

—Matthew 25:36

Stay on the sidewalk, the signs commanded, and we—my mother, my brother, and I—did, not that we were tempted in the very least to stray onto parched grass peppered with fire ant beds and sticky beggar lice and sand spurs. Towers loomed overhead like barbed-wire lighthouses, guards with rifles at the ready, a reminder of an unfathomable life at Tomoka Correctional Institution, a maximum-security facility in Daytona Beach. It was late August, not a tree or lick of shade to be seen; the sapping heat pulsed like a demon. We made our way in a straight line toward the recreation room, a dreary concrete block building, as if we, too, were prisoners.

Earlier in the stark security offices, we exchanged our car keys and iPhones for radios the size of the earliest of mobile phones. In the center of the bulky black boxes was an emergency button, and we were to affix these radios to our waists, but already mine wouldn’t clip properly; the clasp was broken. I clutched it like a walkie-talkie instead. Up ahead, at the sidewalk’s end, a heavy iron door opened, and the smiling face of a tall man in faded blues appeared, and then disappeared. A few feet up the sidewalk later, the door opened again, and before it closed, I saw that the man’s expression was that of a giddy boy at Christmas. It was such an unlikely emotion, so strange in this doomed landscape. I looked up at the armed towers, nervous. Was such joy even permitted here?

The chaplain accompanying us opened the iron door, and we stepped inside to a standing ovation, over a hundred prisoners applauding. We were at Tomoka to honor my late father, a decades-long volunteer who established a Toastmasters chapter there and ran it every Thursday. He’d passed away a month before. Next to me, the hulking, smiling gentlemen who orchestrated this surprise greeting, introduced himself as Jonathon. My father had represented him at a previous, unsuccessful parole hearing. Dad had spoken of him frequently, of how he deserved to be released, and how certain he was of his redemption despite his crime (he never revealed why Jonathon was serving a life sentence). I had never understood that idea, that someone who had committed such atrocious acts could be redeemed. Plus, wasn’t punishment the goal?

As he spoke of Dad’s Thursday visits, Jonathon did not stop grinning. “Bob gave me his undivided attention. When other guys wanted to talk to him, I said, ‘Wait a minute, he’s here to see me!’”

He lifted a worn square of paper from his shirt pocket, the creases evident. It was a note my dad wrote after Jonathon’s first Toastmasters speech. Dad was a pharmacist, his early career in the family drug store in Monroeville, Alabama. He later became a pharmaceutical salesman in Jacksonville and was assigned to a territory that included the Tomoka facility. There was a need at the prison, he learned from staff and doctors. The “guys,” as my Dad always referred to them, wanted to be part of something, something more than what the prison offered. As Dad was an eloquent speaker, the kind of man you hoped made the toast at your wedding or the eulogy at your funeral, he was the perfect person to fill that void. He used Toastmasters to help the incarcerated men find their voices.

Jonathon didn’t unfold the note for us—the advice on that sliver of paper was his and his only—but knowing my dad, it was surely uplifting and encouraging, with a teeny bit of constructive criticism. And to Jonathon, it undoubtedly represented one thing: hope.

~

That was ten years ago. This year, 2025, is a Catholic Jubilee Year. Pope Francis announced that five holy doors in Rome would be opened, two of which he would personally oversee. These ornate doors are bricked up from the inside, and the breaking of the mortar symbolizes, like the ancient Jewish tradition Jubilee originates from, the release of prisoners, forgiveness of debts, and the restoration of harmony in the world. Catholics believe that all who enter pass through the presence of God. The first door was opened at St. Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Eve. The day after Christmas, a second was opened at Rebibbia New Complex Prison. Outside of the church community, this led to some headshaking. A prison? But Pope Francis, known for his outreach to city slums and AIDS victims, as well as for washing the feet of many prisoners, said, “I too, could be here.”

~

After the Memorial service, there was cake and coffee, and we were encouraged to mingle. The service had done a number on me. I wasn’t ready for mingling. I sat off to the side and focused on controlling my tears. A metal folding chair dragged behind me, and then a voice, “You got to stop that.”

I turned around to face a linebacker-sized man wearing mirrored sunglasses. Clearly he spent his allotted free time in the facility’s weight room. He lifted his shades to reveal red, swollen eyes. “Look at what you got me doing.” That made me laugh, and we talked and talked. “I loved your dad,” he said.

I thought that a splash of cold water on my face would help. Someone pointed me in the direction of the restroom, and I walked along the kitchen corridor by the leftover cake and coffee. At a counter, a man sorted through a stack of sketches. I recognized the artist’s style—a heavy crosshatch shading, a light stippling. One of his drawings—the regal head of a tiger—hung on the wall of my dad’s office. The man beamed with pride as he went through the sketches one-by-one. Faces with wide eyes, stern profiles, exotic animals, self-portraits. He selected an unfinished drawing, and deep in thought, leaned against the counter, and began a light crosshatching to make it complete.

I found the washroom and made myself as presentable as possible. The intensity of the day was enormous. If I could have walked out right then, I would have done so. But there were two men I still wanted to meet. Plus, I had no choice. This is an exaggerated comparison, but like the prisoners, I could not simply walk out just because I was tired and emotionally drained. I looked at myself, puffy eyes, head pounding. The cold water did not make me look any better. As I stepped out into the rec room, I was immediately stopped by a young man in his late twenties. “You read my story,” he said.

Years ago, Dad had given me a short story written in pencil on wide-ruled paper. I’d made notes in the margins and signed off with “Keep Writing.” The story was set in St. Augustine, where I live, and he had also lived as a teenager. It was a beautiful love story of a young girl who worked in a sweet shop—pralines, brownies, fudge—on St. George Street, the main pedestrian thoroughfare. As we chatted, I got the idea he wasn’t writing much anymore, so I encouraged him, noting that writing is hard work, and then I stopped myself. He knew hard work. Everything was hard here. What was I even talking about? Fortunately, he changed the subject, kindly asked what I was working on, but as I began, the iron door swung open, and a guard entered blowing a whistle. The room went silent, and without a word, every prisoner found a place, back against the concrete block. Each man was counted, another whistle was blown, and everyone went back—slowly—to what he’d been doing.

I noticed that the writer had positioned himself in the count line beside another young man. His friend looked so familiar—square jaw, dark eyes, a handsome face, a stocky build. I’d noticed him when we’d first arrived, and as the pair, heads together, went back for another round of cake, I strained to see the name on his breast pocket. I did know him, or knew of him. He was also from St. Augustine, and his face had been all over the news in the past few years. He’d been convicted of strangling his wife, leaving her on the beach, waves crashing over her. I watched him, now friends with the young writer; they had their heads together like teenage boys, laughing and palling around. I wondered if they had known each other in St. Augustine, or if their hometown had simply brought them together on the inside. They were like children joking and licking cake icing from their fingers. All around me there were small groups of men talking with my mom and brother, all like old friends or relatives. Collectively, in this room, there was an unbelievable past of horrific crimes and violence, yet there was happiness. Genuine happiness.

I asked around and finally found the two men I wanted to meet, dear friends of Dad’s—James and Jimmy. He spoke of them a lot, but as always, he never mentioned their crimes. Jimmy’s wife had passed away years ago, his grief causing the rage and crimes that had brought him to this place. He had a grown daughter on the outside, and grandchildren. I also knew that he had been very ill recently, but that day he wore an infectious smile. Jimmy was originally from Alabama, and a loyal Crimson Tide fan. My dad was an Auburn fan, and that heated collegiate rivalry had become the origin of their friendship. Jimmy had a folder in his hand, the kind you used in grade school to keep math separate from history, English from science. It was bright green and had been so well taken care of it looked brand new. “This is contraband. Anything you got in your cell,” he whispered. “They can take it away.” He offered the folder to me, as if he were an FBI agent. “Your dad gave me this.”

In the sleeve of the green folder was an orange and blue paper plate with the Auburn University logo. The table erupted in laughter. The week after Auburn beat Alabama in the Iron Bowl, Dad was there for the Toastmasters meeting. After speech practice, dessert was served, and Dad brought Jimmy a slice of pie on that plate. Jimmy thought it was the funniest thing. It was a long-running gag between the two of them, each trying to outdo the other, but clearly Dad won that time. Somehow Jimmy had managed to save the forbidden paper plate in his cell with that folder, passing it off as a document for years. Jimmy would later go on to be released earlier during COVID because of a cancer diagnosis. I often think of him sitting by his daughter’s screened-in pool, drinking coffee in the morning, free to enjoy it where and when he chose.

Though Dad also talked of James, it was more of his work on the inside, his yoga practice and meditation. I didn’t know much of his background or his family. He had severe blue eyes, a confident smile. As Jimmy and I talked SEC football, James had been mostly quiet. Now he looked around the room, and then back at me. “Is this what you thought it would be like?”

“No, it’s—” I said, struggling for the word. “Happier?”

He smiled and shrugged. “Well, in here, maybe. It’s not what it is out there.” He motioned toward the concrete block buildings that housed the dormitories. Some of the dorms could be violent and dangerous, he explained. The radio on my hip was uncomfortable and clumsy. Sometime during our conversation, I’d set it on the table. James motioned to it, and in a serious tone a reminder of where we truly were, said, “Better put that back on.”

“When you get home,” the chaplain told me as we were walking back down the sidewalk in a straight line, this time toward the security offices and the exit, “don’t search for these guys on the internet.” Of course, I would do exactly that. I fell down a rabbit hole at the state’s Department of Corrections site. I discovered their crimes—premeditated murder, armed robbery, assault with a deadly weapon—and then I stopped. I did not need to know the details of their crimes. There was no making sense of their past, no resolving who they were with the sympathy and kindness they had shown my family, and most of all, their respect and love for my dad.

~

On December 26, 2024, when Pope Francis arrived at the holy door of Rebibbia Prison, he stood from his wheelchair, took halted steps, and knocked on the ornate bronze door. It slowly opened, a gesture of easing open the doors of our hearts, and he passed inside. Despite its lack of beauty, I am reminded of that iron door at Tomoka, and the men behind it so many years ago, how they deserve what the pope refers to as an “anchor of hope.” I saw, if only for a few hours at Tomoka, how hope worked its magic—the look on Jonathon’s face, unencumbered by despair and loss, the creased note in his pocket, the Auburn paper plate in Jimmy’s green folder—all of this the outcome of those who have taken the time to bring hope to them.

~

When Michael was released, Dad was there when he walked out the prison door. He drove him to Jacksonville to a family member’s home, first stopping at Walmart where they shopped and purchased new clothes and supplies for Michael to get him started on a new life. Over the years, they had a regular lunch date and talked frequently.

The aneurysm that took my father’s life was not instantaneous. His brain was gone, but his body held on for days. He was a runner, a swimmer; his lungs were strong. He was simply not ready to go, therefore there was time for those who wanted to say goodbye. Michael was one of the first people my mother phoned. While he promised to come to the hospice facility, days went by, and we had not heard from him. One evening, just after sunset, there was a knock at the door. A black man, well over six-feet-tall with gold teeth and a worn leather Bible in his hands entered the room. He had an infectious smile. He came to the end of the bed, took my father’s feet in his hands. With the voice of a poet, he sang out, “My main man, my superman, my Hall of Fame.”

Three hours later, deep into the night, my dad slipped away quietly. I like to believe that Michael ushered him through that portal.

The Assembly Line Flow

Move and manufacture, / produce and progress / till guide, slide, shove / devolves to push, pull, / snap back on a fallen piece.

Steel slab after steel slab

guided, slid, shoved

into a push press

expected to deliver

on loose screws and bolts,

thirty seconds of ear-shattering bangs per sheet.

Bang!

Bang!

Eyes, mind closed to own smoke—

Overheat—

but maintain top speed.

Slow down, breathe—

become obsolete.

Move and manufacture,

produce and progress

till guide, slide, shove

devolves to push, pull,

snap back on a fallen piece.

Till each steel slab

on assembly line's flow

spawns a sob

masquerading as a rattled screech.

Bang!

Bang!

till screaming prayers to remain composed—

on shifts one through three—

looped on an endless repeat.

Rex

In the summer / we swiped at the sun / laughed until our sides hurt / Brave as kids could be

We're proud to feature this poem from Van G. Garrett’s chapbook Chinaberry Constellations: Odes, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist of The Headlight Review’s 2025 Poetry Chapbook Contest.

Big Mama’s house was two floors

of adventure:

A library of memories

A storehouse of stories

A patchwork of possibilities

Walls with hidden treasure

Creaking steps

A haunted attic

Photos and old records

In the summer

we swiped at the sun

laughed until our sides hurt

Brave as kids could be

Except for when we hard-sprinted

from a German Shepherd

with amber-colored eyes

named after a dinosaur

ACCESS_DENIED: heart.exe

Emotional drive: / fragmented.

> Running diagnostics...

Emotional drive:

fragmented.

Accessing main directory:

/hope/memory/you

Status:

file: touch.exe — missing

file: laugh.wav — corrupted

file: promise.txt — overwritten

folder: trust/ — access denied

Attempting repair...

Error: permission denied.

System prompt:

“Feeling requires vulnerability. Proceed?”

User input:

...

Suggested action:

abort.

Some systems forget

how to open again.

On the Death of a Queen

there is laughter like the ripples / when something dark breaks the water, / the laughter of children colliding

with the inert thigh of their mother / stood hollering

there is laughter like the ripples

when something dark breaks the water,

the laughter of children colliding

with the inert thigh of their mother

stood hollering,

there is the laughter of that discovery

of looking up at the mother’s face softening

and learning fear is a thing

you grow into

not out of,

there is the laughter of wind filling a sail

and two lovers’ hands on the tiller,

peacocks pluming and the dogs’ mistress returning

to a forest of tails around the hearse,

there is

the laughter of doors opened slowly by lovers

with a bottle in one hand and a lie in the other,

then the dark laughter of the same door closing some hours later,

the laughter of disbelief and crumbs in the bed,

there is

the laughter of the town crier drunk in the night

swaying under a lit window

where

the pert whisper of a curtain being drawn

seems louder than the tolling bells.

Scooch

The lower I scooch, the better the reception. / Like the signal’s intensity is what it is except / around me.

The lower I scooch, the better the reception.

Like the signal’s intensity is what it is except

around me. We’re watching The Rockford Files

in my father-in-law’s recreational vehicle in a

private drive in Ft. Lauderdale, James Garner /

Jim Rockford handing out uber-macho lectures.

It’s 1980. I’m a new dad and reading Faulkner

for a class. I catch the politics of calling women

Honey. The woman in tennis whites has framed

Rockford for felony murder. Her navel, an innie,

packs loads of social import before its vanishing.

Arthur Dixon, my kind father-in-law, stands. He

steps to the antenna. Now he’s motioning Scooch,

Jim Rockford smart-mouthing his way to triumph,

the rest of our family inside the house or at church.

This evening, Arthur loves his battery-powered TV,

asks if I like Florida. I say, Positively, as Rockford

calls up William Faulkner in a ’74 Firebird Esprit,

skillfully spinning a steering wheel—like America

is okay just fine but you need to be willing to, well,

scooch down so you catch sight of the road ahead.

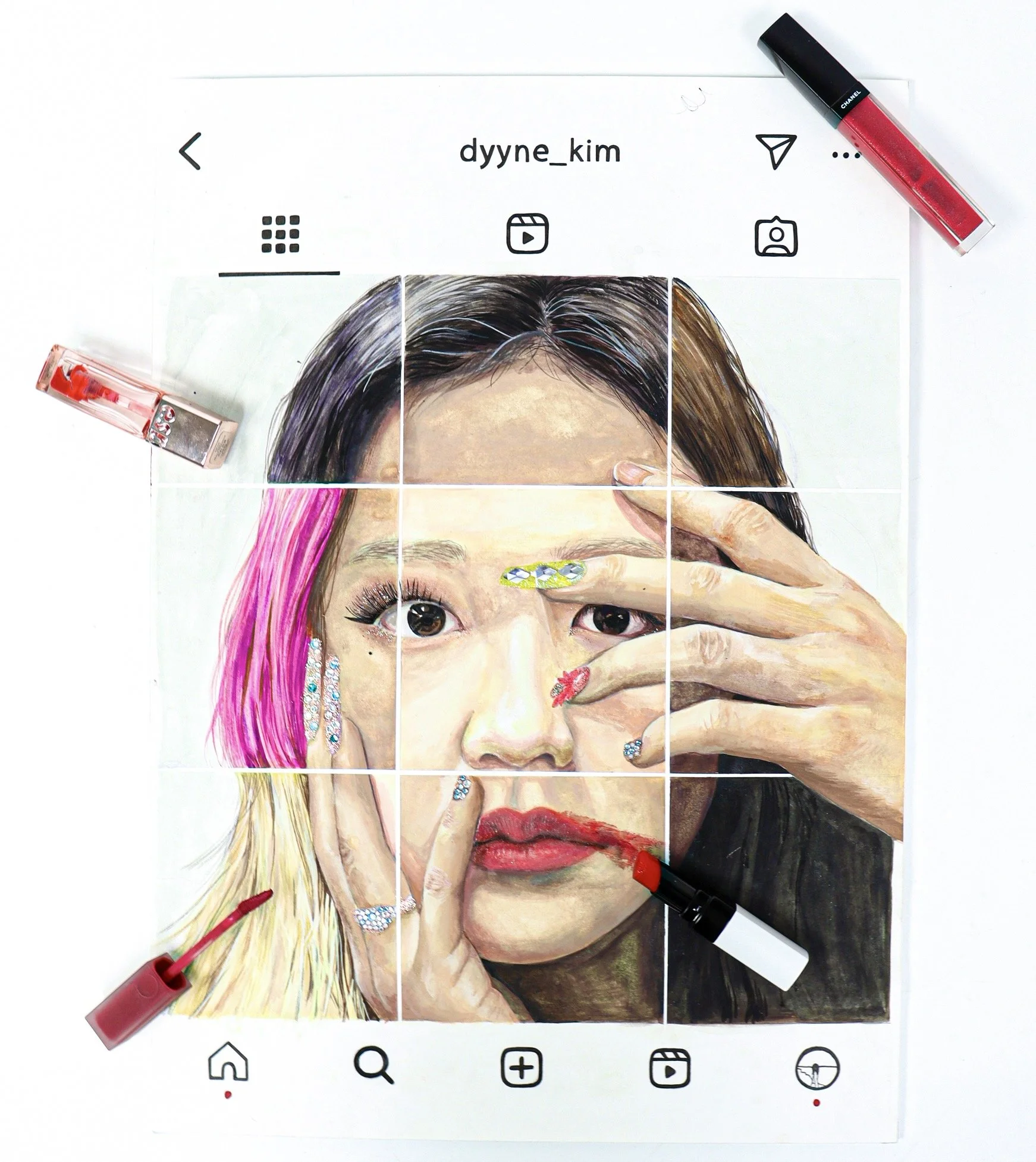

Two Paintings

Artist’s Statement

Inspired by René Magritte and Daniel Arsham, I always present contrasting planes of existence in my paintings. To me, “dream” and “reality” are fluid constructs; our perception constantly shifts in response to what we see and feel. This ever-changing perspective is what draws me to art as it also serves as my bridge to empathy. While themes of inequality may not be immediately apparent in my work, they emerge through a hopeful lens, a belief that art has the power to transform how we see and engage with the world. By merging the extraordinary with the everyday, I aim to spark imagination and optimism. What may seem monochromatic to some is a vibrant color in the sky for others, and through my work, I hope to offer that sense of possibility—an invitation to escape negativity and see differently.

Pennypoker1919 to His Followers

Welcome to my playground sanctuary, friends/fans. This room is an extremely passionate and sensual place filled with mystery, desire, masculinity! I am permissive and open, live to be in front the webcam. Please play along and look at the bright side.

Welcome to my playground sanctuary, friends/fans. This room is an extremely passionate and sensual place filled with mystery, desire, masculinity! I am permissive and open, live to be in front the webcam. Please play along and look at the bright side.

My tip menu, dears:

Send me 1 token lol if you enjoy * 2 if you love * 10 for flash my stuff *

30 foreskin massage * 60 explain you my 53 seduction tattoo in ethereal detail *

70 intellectual conversation * 100 special armpit entertainment *

200 open window for view of downtown Kharkiv * 250 confirm theory that I look like

Timothée Chalamet * 500 virtually you sniff my bushy base * 1000 body tour *

1,500 we listen to the air-raid sirens * 3,000 I ship my underwear to your door anywhere *

4,000 seven somersaults in city rubble * 5,000 after the bombs, watch dawn over Kharkiv *

6,000 I introduce you to my hamster * 8,000 intellectual conversation plus *

10,000 become the god of my castle * 20,000 we meet in Kharkiv, you and I, for a night

of body contact only * 40,000 I take you around on my motorbike and you hold me where you

have need to * 50,000 real life body tour + armpit entertainment + bike tour + intellectual

conversation * 100,000 roommate life with you in your country after the war, you house and clothe and feed me and teach me the language and bathe me + unlimited intellectual

conversation + armpit entertainment + long tongue games + every orifice explored + 20 new tattoos *

500,000 I read to you what genre book or mystery you desire, I wash your feet and go for your shopping, we marry, you explore every orifice + intellectual conversation + Maserati convertible + I clean, do house jobs and fixing + unlimited foreskin massage, hundreds of handstands and somersaults

**************1,000,000!************** I belong to you, my every orifice for your curiosity and whim, even after my passing of twink years and you pass into aged years, I feed you, clothe you, bathe you, nurse you and wheel you, and when you’re disappeared I arrange all and inherit all and bring flowers, whichever you command, and keep the earwigs out of vase by your headstone as long as I am able and forever, my love.

Breakout

As soon as you reach a hand through them, / the walls will dissolve.

As soon as you reach a hand through them,

the walls will dissolve. Work with

the window there, above your eye-level.

Even if you have to stand on your toes

until your arches throb, become

a part of what you see through the bars:

the alley where snow hangs on in smears

under bare trees, garbage trucks

pack the sodden refuse, and a grey-striped cat

skirts the puddle under a downspout.

Your window will enlarge until it replaces

the entire wall, and you will walk out whole.

Memory of Exodus

may / these / bones / hold fast / to the / ticking before the / quitting

may / these / bones / hold fast / to the / ticking before the / quitting / we weren’t born a haunting / through numbing or rowdy melancholy / what we inherited meant to drown us / lungs ablaze we gripped / survival continuing as / prophetess spilling radiance / staving disaster determining fate / beyond an algorithm branch / few things are growing / faster from collapse / a dwarf star / uses its energy / before / imploding / our skin was / the night sky / containing / it

final sale: no returns

shelf life / expiration date / say you love me before the price tag peels off

shelf life

expiration date

say you love me before the price tag peels off

[aisle 13, fluorescence flickering—]

you reach for the last dented can of chickpeas & so do i & so we do

& suddenly our delicate hands are tangled like a broken barcode…

like an error in the quick scanner—like a misprint on the receipt of fate.

(does fate even issue refunds?)

the can rolls & gravity takes its tax—bottoms out—bottoms out—out. out. out. we both bend

down, the linoleum yawns. an abyss in the waxy white tiles. (buy one get one free. but

who is one and who is free?) a voice on the loudspeaker crackles: attention shoppers,

all prices are final. but my knees are on clearance—your laughter is marked

down—our shoulders gently brush & suddenly, the barcode of your

wrist is scanning my pulse. i’m full of expired metaphors. you’re

full of unspoken coupons.

(fine print: offers valid while supplies last)

the manager’s voice rustles overhead, a plastic bag in the wind. the fluorescent lights glitch.

the can rolls towards the underworld of the shelves. disappears. the lowest shelf. (where

forgotten things go. where we’re going. where we—) you giggle—you giggle—

you peel the last digit off a price tag and whisper it into my ear like a

prophecy. i mishear it as love. and then all markdowns,

we disappear in the bustling crowd.

(reduced for quick sale)

but then—

i wake up in aisle 13 again. again. again. the same can waiting. you reach. so do i. the scanner

beeps. the loop begins again. (does fate even offer exchanges?) the can rolls—but this time

it doesn’t stop. it keeps rolling, past the lowest shelf, past the waxed linoleum, past

the storeroom door left ajar. down. down into the supermarket catacombs

where carts with rusted wheels hum lullabies and lost items mutters

fainted names. (who is lost? the can? us?) you follow it. i

follow you. a door abruptly closes behind us. the

intercom gives a ding: attention shoppers,

this store is now closed.

and when we returned around—there is no aisle 13…13…13…

no fluorescent light—no way back. only shelves stacked

high with things we do not remember losing. And

shadowy price tags that bear our names.

this item is no longer available.

(final sale. no returns.)

On the 56th Anniversary of My Father’s Death

I decide to join the resistance against negativity. / To celebrate that cancer is a chronic illness now. / And that an old family friend will be able to live / with his blood cancer, stage four.

We’re proud to feature this poem from Elizabeth J. Coleman’s chapbook On a Saturday in the Anthropocene, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist in The Headlight Review’s Chapbook Contest in the Spring of 2025.

I decide to join the resistance against negativity.

To celebrate that cancer is a chronic illness now.

And that an old family friend will be able to live

with his blood cancer, stage four. In my mind,

I bestow on him the joy of knowing his sons’

spouses and children. Then, just as I do every day,

I empty our compost bin into our building's

larger one. Tuesdays the sanitation

department picks the compost up, and, after

a while, the resulting soil will go into New York

City’s parks, or so they say. The songbirds

are returning to Riverside Park, with their

capacity for human speech. My beautiful brown

dove is back, just four feet away, on my office

windowsill, watching me work.

Later we’ll head to Central Park, and, I hope,

come upon the saxophonist playing under

Graywacke Arch. My grandson

will skip over, put money in the case.

Last week, my freckled granddaughter

sold me a hand-painted bookmark

at her Ukraine fundraiser, with pink and blue

flowers, a sun, and a sky of paper white.

And today the woman who owns the frame store

between 95th and 96th on Broadway told me

she wants to go to outer space, as she smiled

from behind the counter in her little shop.

I pictured her en route in her white top,

leopard print leggings and black flats.

Love Song Intended to Stave Off Discontinuation of Relations (Unsuccessful)

I’ll be your boy toy!

Say you want me

And I’ll be your boy toy

If you want me hard to get

I’ll be your coy boy toy

If you want me Scottish

I’ll be your Rob Roy boy toy

If you want me to swell and sway with the crowd

I’ll be your hoi polloi boy toy

If you want me strong like copper and steel

I’ll be your smelted alloy boy toy

If you’re Jewish and I’m not

I’ll be your goy boy toy

If you want me saucy like Szechuan beef

I’ll be your Kikkoman-smothered bok choy boy toy

If you want me After the Thin Man

I’ll be your William Powell and Myrna Loy boy toy

Or, if you want something that melts in your mouth

Slavic and sweet (and you don’t mind

sharing the bed with crumbs)

I’ll be your Bolshoi Ballet/Chips Ahoy! boy toy

Letter from the Managing Editor

As I approach the culmination of my degree, I have gone through various iterations of a capstone idea. Perhaps a collection of short stories, a novel, a novel written through short stories.

As I approach the culmination of my degree, I have gone through various iterations of a capstone idea. Perhaps a collection of short stories, a novel, a novel written through short stories. How many perspectives should I include? Would one be too limiting? Would six be egregious? And, of course, at the crux of it all, the age-old question: what is the story that wants to be told?

Needless to say, it’s been an ordeal trying to figure out the answers, and it would be an understatement to say I have been nervous about all of this. I wanted to start early, get a head start on what I’m aiming for in the fall so I don’t stumble too often. This summer, however, I’ve pivoted much of my energy from capstone prep to my work at The Headlight Review. It’s had me contemplating a great deal about what the submissions we’ve accepted do to grip me, what I can learn from them as I gear up for spelunking the depths of my creativity.

My favorite part of my working on this issue has not simply been copyediting, reformatting, or proofing, but the engagement I have had with the authors, poets, and artists. Corresponding with the person behind the work is my favorite part of any role in editing. If you know the creator, you get to know the piece better, understand the nuance of what they want to say and how they want to say it.

And there I found it. The core of what I need to do to understand my capstone better. And it’s the same invitation that countless literary magazines send to potential contributors: Share a composition that is uniquely yours, that only you could ever create.

Will oil or gouache better convey the way your eyes funnel sunlight? How many characters are needed to express the complexity of your grief? Does the line need to break at a different point to give the impact you desire? The varied and unique answers to these questions are what set each of these pieces apart from the rest.

Captured within this issue of The Headlight Review are three fictional stories, five nonfiction pieces, the visual art of four artists, and the work of a whopping twenty poets, which includes our Chapbook Prize winner and finalists. Each contributor to this issue has a distinct narrative to share, one that only they could ever do justice by sharing it in their own unique voice. It is my greatest hope that you, reader, will absorb each of these pieces with compassion and care, knowing that they, in all their complexity and nuance, came from real people.

To our contributors, I’d like to extend my gratitude for making this experience so enjoyable. To Brittany Files, thank you so much for your guidance toward my start in this role. To the whole THR team, thank you for the warmth with which you’ve welcomed me onto the masthead.

And to our readers, I hope this issue inspires you to walk your stories past the page, your poems through time and space, your art over the edge of the canvas. To share your stories with the world and let them find themselves at home somewhere beyond your mind.

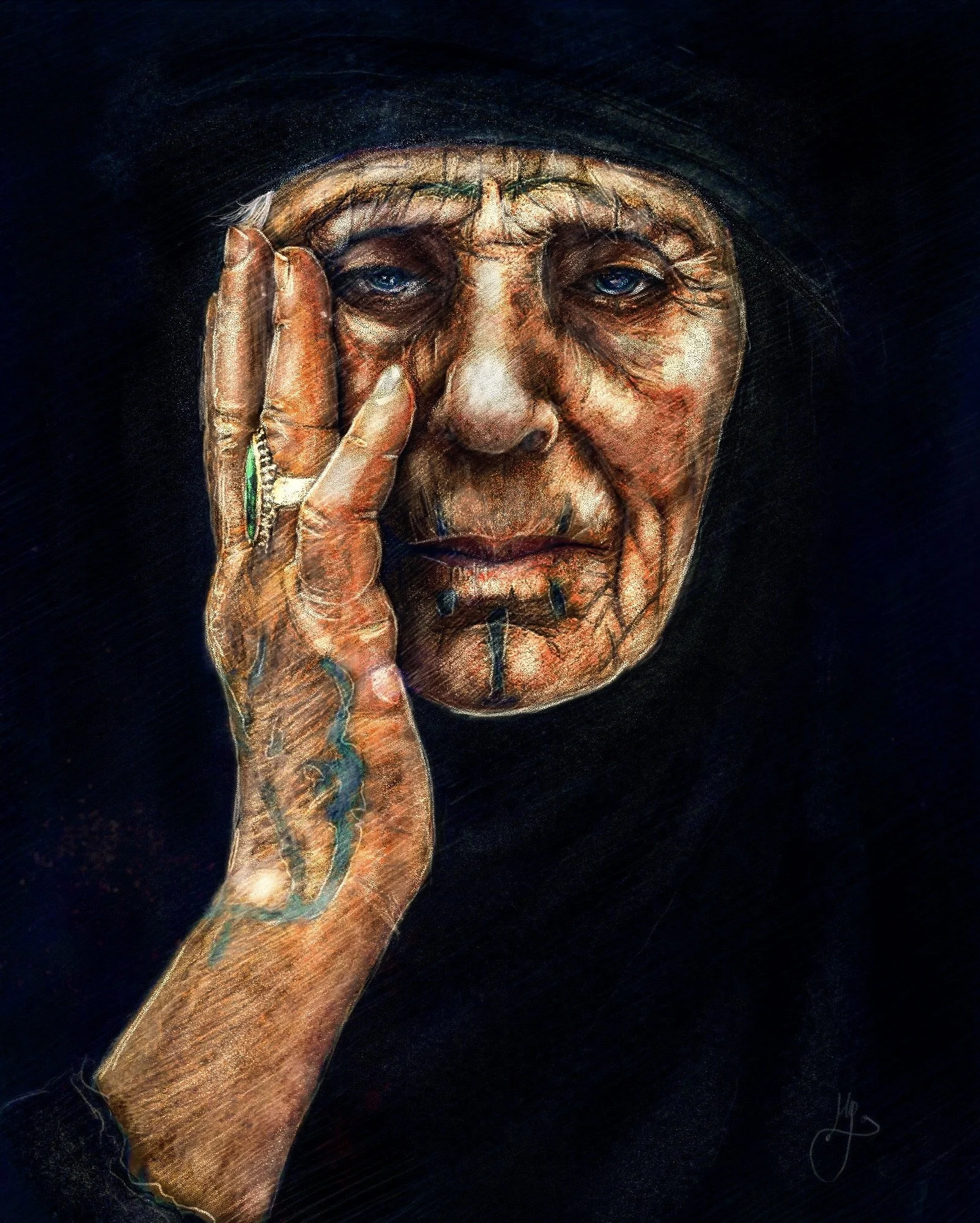

Two Paintings

Artist’s Statement

Gorjian’s work focuses on digital painting, GIS, and urban design, reflecting themes of tradition, identity, and resilience. Through her art, Gorjian aims to bridge past and present, using digital tools to document and celebrate cultural heritage. She has exhibited her work nationally and internationally, engaging audiences in conversations about history, storytelling, and the evolving role of digital media in preserving tradition.

Still Standing

After over fifty years, Warren and I began corresponding—a term I use loosely, as Warren does not write. He does not speak. His IQ hovers below 20, and he does not know who I am.

After over fifty years, Warren and I began corresponding—a term I use loosely, as Warren does not write. He does not speak. His IQ hovers below 20, and he does not know who I am. This is an excuse I saw my parents embrace most of their lives to alleviate the guilt of no contact, of giving up their parenthood, when it came to their fourth child and firstborn son.

Warren was about two years old when it became increasingly evident that something was wrong. He would spend hours sitting on the floor, with his head against the wall, rocking back and forth as if keeping time with the ticking of a metronome only he could hear. His hair had worn a little bald patch in the spot where it met the plaster. Words were not spoken; words were echoed, much like a parrot mimicking what it heard. No words came out of their own accord. No babbling two-year-old banter, the type we parents sometimes complain about. I’m sure there was no complaining by my parents. Only worry. Enough worry to make appointment after appointment with specialist after specialist. Diagnosis: Severe Mental Retardation. Age three.

~

“The Benches” was the place all the mothers of the building would meet with their toddlers and strollers to socialize and gossip. It was a long strip of a park adjacent to Henry Hudson Parkway with benches extending a city block. I remember playing there as a child with dozens of other kids from the building. I have very few memories of my childhood, but “The Benches” I always remember as a safe place. I have had recurring dreams in my adult life of various scenarios where someone is chasing me, trying to kill me, etc. I always knew that if I could just get back to “The Benches” and lay down on the concrete, I would always wake up in my bed. I would be safe.

Mom was embarrassed to have the other moms see her son, who was not quite the average child. So, instead of her usual routine with the older children, of going to The Benches with the other mothers, she would take Warren in the stroller and walk for hours, she told me, so her baby would not be seen, and apparently, she would not be embarrassed. It was the 1950s, but it is still hard for me to fathom.

The doctors, the specialists, and even the Catholic priests would all weigh in. It was decided that the best thing for all would be to place Warren in a home for the mentally ill. The decision was made that Warren, not yet four years old, would be sent to one of the best private institutions in the Greater New York area. I remember driving north, up the tree-lined Saw Mill River Parkway every Sunday afternoon to visit Warren. I was eight.

We would go to the Carvel ice cream stand down the road. Sad but true, this is the only concrete memory I have of my brother. Carvel on Sundays.

To be fair to my parents, it is what you did in the 1950s. Your pediatrician suggested it, and all the specialists recommended it. Many families faced these same choices. For some, it was a deep, dark family secret, not even knowing that their sibling or relative even existed. For others, there would be weekly visits. I know it was not easy for any of them.

My father was manic-depressive in the days before lithium. With three children of my own (all born within twenty-seven months of each other), I have often wondered, what would I have done? There are those who say that the parents were ashamed. Others say they just threw their children away and forgot about them. I do not pretend to know the answer. Unfortunately, what goes up must come down. The mania of my father, along with his record-breaking sales performance, came crashing down. When my father was in a manic stage, he could sell ice to the Eskimos. He was hospitalized, and the income dried up. The private institution had to give way to a state mental hospital, maybe the three most dreaded words in the English language.

Warren was transferred to Willowbrook State Hospital on Staten Island. It was actually called a school, and it was the largest institution for the developmentally disabled in the world at the time (and that was not a good thing).

~

My brother spent about fifteen years of his life at Willowbrook, the place that Robert F. Kennedy called “a snake pit” in 1965. When Kennedy visited the site, he was horrified by what he saw and stated that “individuals in the overcrowded facility were living in filth and dirt, their clothing in rags, in rooms less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in a zoo.”

A combination of budget cuts by Governor Nelson Rockefeller and more demand for placements coupled with indifference led to most of Willowbrook’s problems. Some quote a ratio of seventy patients to two or three caregivers. I wonder how those caregivers could keep clothes on the backs of children with mental disabilities as severe as most residents, who would disrobe as fast as staff could dress them. How could they keep the feces and urine cleaned up when there were seventy other children to look after?

I visited Willowbrook once. It may have been more than once, but the first visit is all I can remember. It was the Fall of 1970. I was twenty years old. I had been visiting my brother from the time I was eight years old. My two sisters, ages 4 and 9, and I, would pack into my parent’s car and drive the half hour or so up the tree-lined highway to Ferncliff Manor in Yonkers. It was a beautiful place with acres of grass. We would lay a blanket out and have a picnic with our brother. We would run around and play, especially my younger sister, as they were the closest, only about a year and a half apart in age. She missed her baby brother.

Willowbrook, on the other hand, was far from the pretty, peaceful picnic grounds of Ferncliff. The antithesis. When I first entered Willowbrook in 1970, I was with my father. My mother would not or could not return. My senses were bombarded. The scent was sharp. A mixture of bleach and feces. The air was still. The halls were dimly lit so as not to see the chaos or the peeling paint. The sounds I could not quite place: murmurs, distant cries, quiet humming, the shuffle of feet. There was a sense of stillness that felt anything but peaceful. I had not prepared myself for what I saw that day, but even then, I had the sense this place was failing the very people it was meant to be helping. A kind of numbness settled in—not because I didn’t feel it, but because I felt too much and didn’t know where to put it.

It wasn’t chaos. It was something softer and harder to bear—indifference. Neglect masked by the very rhythms of daily life.

That day left a lasting mark. It didn’t just shape my view of institutions—it asked me who we become when we are unseen. Does Warren know he has a family? A majority of the residents there have no visitors at all. Unfortunately, I did not pursue those questions or those feelings I had that day, for many years. I buried them with all the rest.

It breaks my heart when I look at this photo taken when Warren was just a few weeks old because I see such hope. Children with such great prospects, immense potential. A future not yet marred by illness and tragedy. We were all unaware of what lay ahead.

It saddens me now because I know the outcome. I lived through it. The memories feel like a slow echo that never quite fades. There would be two more children to come, and the youngest would, in essence, never have the opportunity to know two of her siblings pictured here. In fact, she was not even told of their existence for years.

Lorraine, my older sister on the right would become affected by schizophrenia in her teenage years and commit suicide in 1967. Warren, the newborn in momma’s lap, would be institutionalized by the age of three, and dad, the photographer, unbeknownst to me at the time, would suffer from Manic Depression/Bi-Polar I for the rest of his life. I was sixteen years old when lithium became FDA approved for his type of mental illness. I didn’t fully recognize my family situation for many years. Like all small children, I perceived my life as typical. Of course, it was the only family life I had known. I used to think I had a perfectly normal childhood growing up in an upper-middle-class family in a particularly good neighborhood of the Northwest Bronx. Still, all is not always as it seems.

So, it has been fifty years since that day at Willowbrook. Fifty years of distance is not just a timeline; it’s a slow layering of choices, silences, rationalizations, and even regret. I had always blamed or perhaps rationalized my parents’ behavior for not visiting and for moving 2500 miles away. But what about myself? Was it guilt for not challenging the patterns my parents set? Was the guilt shaped by family dynamics and motional survival?

When you believe someone doesn’t recognize you, especially someone you’re biologically and emotionally tied to, it can feel like the connection was broken before it even had a chance to be made. “What’s the point? He wouldn’t understand. He wouldn’t know me.” But underneath that logic is a powerful current of loss—not just of a relationship, but of significance, visibility, and possibly identity.

Saying “He didn’t know who I was” may have been a way to protect us all from pain. There’s grief for what never existed: no history, shared memories or stories passed between siblings. And that grief is quiet. It just lives silently under decades of rationalization.

~

Since 1985, at the age of thirty, my brother has been living in a group home in upstate New York. The Consumer Advisory Board (CAB) monitors his wellbeing, which provides necessary and appropriate representation and advocacy services on an individual basis for all Willowbrook Class members as long as they live.

Warren has been well taken care of for the past thirty-eight years of his life. He has his own advocate who makes sure that all the stipulations of the Willowbrook Decree of 1975 are being followed when it comes to someone from the Willowbrook Class, as is my brother. But I often wonder, what about the trauma of the past? What does he comprehend of the horrors of growing up in an institution such as Willowbrook?

I am in contact with his advocate as well as his local case worker. They say he seems happy but does tend to withdraw and isolate himself. He doesn’t trust people very much. I suppose I can’t blame him. He is electively mute. Not to mention that Warren is missing the tops of at least six fingers, and, sometime in the past, his nose has been broken. Warren also has no teeth. I read an account of a Willowbrook parent stating that the Willowbrook dentist was notorious for pulling teeth. Her child had no teeth because she would bite herself until she bled. Whether this is connected to Warren’s missing fingers or missing teeth or is a result of abuse or self-mutilation remains a mystery.

~

Warren loves classic rock—a man after my own heart. Music therapy is essential in the lives of the mentally disabled, probably because music is nonverbal. It transcends language. My brother is nonverbal, and I like to think that the music he listens to speaks to him in some way. I know that music calms anxieties and relaxes us when we are overstimulated. I’m told he can spend hours sitting in a rocking chair on the back porch of his group home in Plattsburgh listening to his CDs: He likes everything to be in its correct place, such as furniture being arranged in a particular way, or the house phone hung up in a certain direction. They say he can be quite helpful in clearing things away, such as mats after PT, arranging and clearing the living room after various activities. Sometimes, amusingly enough, his arranging can happen while the activities are still in progress! This brings a smile to my face!

Warren has a personal savings account that cannot accumulate over $2,000. When the account gets up there, they go shopping to spend it down. His basic needs are taken care of, so he can shop for things he especially likes. His caregiver said Warren has the most expensive taste of any man she’s ever met. They will go to JCPenney, and he will go directly to the silk shirts or the most expensive items they sell. He is a very “interesting and complex” person, she says. It shows the respect that he garners as an individual, not simply someone or something to be taken care of. Not forgotten.

~

It had been fifty years since I saw my brother, The last time was that visit to Willowbrook in 1970. Not long after, I left New York for the west coast at about the same time my parents left New York. While my mother was alive, she would get annual reports on his health and progress and always shared them with me.

My youngest sister, Stacey, had never met Warren. He was institutionalized eight years before she was even born. She can’t quite remember when she was told that she had another brother. It was probably when she was about seven or eight years old.

When I brought up my plan, she was hesitant at first, but we finalized our trip and met in Montreal for a three-day visit before driving to Plattsburgh, New York, together in October 2023 to meet our brother. We had also arranged to meet both Warren’s care manager and his advocate from the New York State Office for People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) for lunch in a nearby café.

I was heartened to learn of the care that the State of New York is giving to those with developmental disabilities and the extra care for the “Willowbrook Class.” Meeting these two women in that café was proof enough of the care and concern that my brother is getting. They spent two hours with my sister and me talking about Warren, listening to us recount our own family history, and answering any questions that they were able. They could not have been more caring and sincere. I am so grateful to have met them. Not only did they spend those two hours talking with us, but they also went with us to meet Warren. He was familiar with both, so they carved out even more of their busy days to come along.

We arrived at the house on Turner Road. It was out in the country among the trees. The feeling was peaceful and bucolic. His house manager greeted us and let us know that the other housemates had gone out so that we would have more privacy and less chaos.

There are four male house members. I believe at age sixty-eight, Warren is the oldest. Two of the men are more high functioning and a bit outspoken, while Warren is selectively mute and very low functioning. The fourth member falls somewhere in between, and it all works.

The house manager told us that Warren had just gone to his room to lie down. His advocate went and peeked her head in his room to say, “Warren, you have some company. Do you want to come out and say hello?” No response. His habit is to get into his bed with his legs crossed in a yoga position, then pull the blanket over his head and lie down. He looked like a not so little cocoon. I then said, “Hello Warren, I brought you a present,” and he immediately popped up from his bed and ran down the hall to the dining room table. He moves very quickly (and apparently even quicker when there is a present involved).

A bit later, we went out to his favorite spot on the porch where he sits in his lounge chair to rock and listen to music. We went through his box of vinyl albums sitting next to the record player. I was a bit surprised. I had to laugh and think, He’s a man after my own heart. There was Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, The Beatles (his favorite) and even AC/DC and Metallica!

So, Warren came out of his room to get his present. I brought him a Seattle Sweatshirt, as I know he loves sweatshirts. He went straight to the kitchen to get strawberry milk. The house manager poured his milk and then let him pour in the strawberry syrup and mix it up. They brought it to the table where he gulped it down as fast as he could and some of it spilled down the front of his shirt. All those years at Willowbrook ingrained in him that everyone would steal his food if they could, so eating or drinking as fast as he could was the only way to protect it. To this day, he must have someone watch him eat so the food doesn’t go down too fast and choke him. When a new member of the household is added, Warren will either bring his food to his room or else put his arm around the plate, protecting it from the would-be food thief. Once he is comfortable with the new house member, he will come back to the table for meals. It has been thirty-eight years since Warren left Willowbrook. Habits die hard. I only wish I knew what other horrible memories reside in his brain from spending his most formative years there.

He came to the dining room table and sat across from me.

We looked at each other. There was a connection of some sort. I asked if it was alright to take a picture. His advocate asked Warren if it would be ok, and he immediately jumped up from the table. I thought, oh no, he’s going to run back to his room, and turn back into a cocoon. To my surprise, however, he stood up, went to the middle of the room, and looked right at me, as if to say, “I’m ready for my picture now.” I thought I would quickly take advantage of the situation and handed my phone to Stacey and asked her to take a picture of both of us. I nonchalantly went over and stood next to Warren.

At one point Warren grabbed my arm and started pulling me towards the kitchen. I thought this was a real moment between us, but it turned out, he wanted more strawberry milk. When I realized, I just laughed and said, “Oh, he’s just using me.”

We had a total of twenty minutes or so until Warren decided to go back to his room, get in his bed, and pull the blanket back over his head. Stacey, for the most part, stayed in the background. But I know she was as moved as I was by the whole experience.

He reached out and touched my hand once. I really believe we did have a connection, my brother and I. I now have a new and wonderful memory that is gradually replacing the dark one that haunted me for fifty years.

Excerpt from Salt Bones

An excerpt from Salt Bones by Jennifer Givhan (Mulholland/Little Brown, July 2025)

The Salton Sea,

Southern California

An excerpt from Salt Bones by Jennifer Givhan

(Mulholland/Little Brown, July 2025)

___________________________________________________________________________

Thick, noxious air burns her throat as she flees through the fields, mud clotting to her soles like leeches, one untied shoe after the other over the rutted vegetables.

She shouldn’t run toward the water—it isn’t safe. But the murk would offer cover.

She doesn’t risk a glance behind her or fumble at the yellow onions bulging from the ground. At first, it’s the familiar stench of sulfur bubbling from deep in the earth, mangled with the smell of rotting fish, thousands of carcasses gurgled onto the brackish marsh just ahead.

Then something intoxicatingly sweet fills her nostrils. She’s not near the sugar plant on the other side of town, but those sugar beets smell like overripe dirt anyway. This is more walking into the donut shop at sunrise and ordering a maple bar and sweet tea. She shakes her head, sure her blood sugar’s collapsing from starvation and dehydration and she’s about to nose- dive into the fields when the sweetness sours just as suddenly as it came—and she’s overtaken by the dank stench of sweat and shit.

Her heartbeat throbs in her ears, eclipsing the sound of a truck engine’s roar—another predator in the night, tearing through the furrows and ruining the crops, chasing her.

Would anyone hear her if she screamed?

She can’t waste the breath she needs for running.

In the distance, golden lights twinkle a mythical city arisen in the nowhere between the closest towns, neglected or desolate, and the still-living, breathing town where her people are.

But the lights aren’t magical, and they’re far, much too far. She’d never outrun the truck to get to the geothermal plant where someone at the gate might hear her. Let her in. But would they believe her if she told them who was after her?

A few hundred feet ahead stands a dock. Rickety and slanted, but still possible cover. She could jump into the frothy, stinking water, hold her breath, and hide beneath the battered, salt- crusted planks. Her pursuers might assume she’s darted toward the wildlife preserve, climbed the chain link. Or drowned.

The fug of gasoline and exhaust commingles with the acrid sea, fertilizer, her own sweat and spit, and her blood pumping, pumping furiously. Her lungs scream. Don’t let me die out here—

The sky lights a purple path upward—the Milky Way beckoning as if someone’s holding a flashlight behind a pinpricked cosmic bedsheet. It cascades across the expansive blackness that blurs into the jagged peaks of the Chocolate Mountains beyond this stretch of desert that’s claimed countless lives.

The clomping of hooves and a blaze of headlights pierce her back. Her dark hair flaps crow’s wings against her sweat-drenched hoodie as her high-tops slip against the mud.

There’s nowhere to hide, no tree cover, nothing but shrubs and dirt, and the green fingers of onion bulbs wavering the hands of the dead, reaching for her, grabbing, pulling her downward.

She falls to her knees, blackening her hands with soil.

But the creature canters steadily toward her.

She scrambles up, the Salton Sea in sight, a soupy bog in the darkness.

Her feet crunch fish bones and the minuscule shells of dead crustaceans; millions of them crackle beneath her while she flies toward the pier stretching into the abandoned lake, all that “accidental” water sloshing for miles across the dusty bowl of valle, before the headlights overtake her, and the horse-headed woman cackles, her midnight-black mane scraggling down her bare back.

For a moment, she’s glowing yellow, gleaming with beads of sweat. Saintly.

Then the gunshots resound.

One. Two. The deafening booms reverberate through the mountains. Aerial drills. Only this is no drill. Following the shots—metal clanks its sick click, click. Boom, click, click. Boom.

If anyone were out here but the night animals, the stars, they’ve shut their eyes.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Jennifer Givhan is an award-winning Mexican American and Indigenous poet and novelist from the Southwestern desert. To learn more about her upcoming fourth novel, Salt Bones, from which this excerpt is taken, read our interview with Givhan in conversation with Mary McMyne in the “High-Beams.”

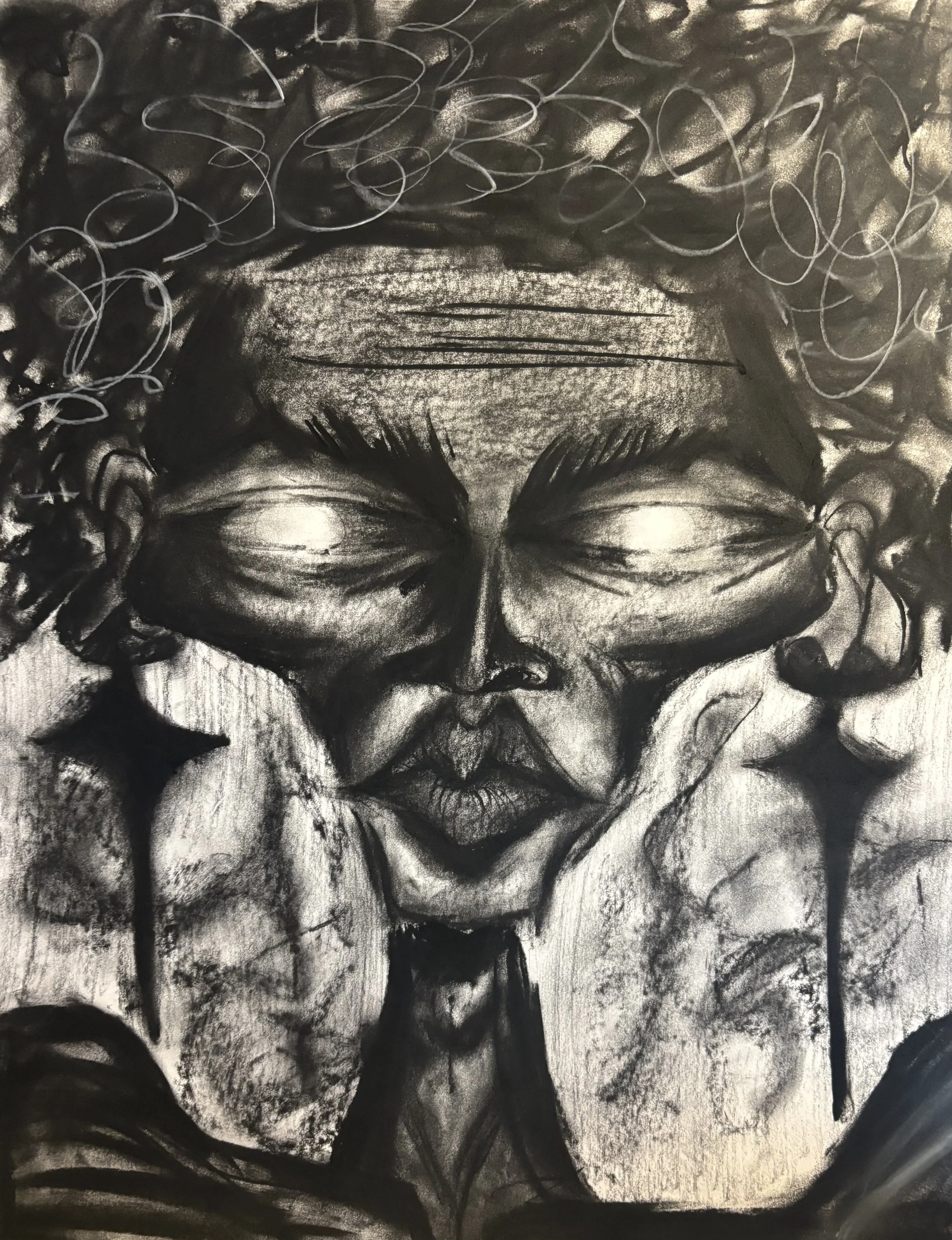

Three Drawings

Artist’s Statement

I believe art is beautiful because it is liberated from any ties to ‘practical’ usefulness or productivity and instead exists only to provide radiance to life. Visual art is an escape from the utilitarian movements people become so accustomed to. I want to visually express what queerness is, find the ideal form, the spirit of queer people, and present it in a way which others can understand the elegance and taste of.

Two Poems

see, the beech tree / never asked to be made palette / for the

lovebirds / armed with blades / gashing their runes / into the bark / scarring trunk / initials standing out / standing tall / for love

it is a burden to know;

it is a given to fear

teeth upon bone. blood upon snow.

skin upon skin. worry upon face.

face upon sheets. repeat then repeat.

bandage the wounds but return to the teeth.

return for more. the wound is not

a badge of the love you once received,

but it feels close enough to warrant

another tear of your flesh, another seep

of your fluids. the wound is not

a badge of the love you once received,

but it is all that awakens your

senses. the days are many but

the moments of awareness are few.

in the morning drops of dew, count

the moments you feared would pass

you by. they already have—maybe.

it is a burden to know. it is a given

to fear. when december comes knocking

at the window, knuckles chapped

in the biting wind, what answers will you have,

what lessons left to share?

someone once told me to understand

love as disease / love as invitation / see, the beech tree / never asked to be made palette / for the lovebirds / armed with blades / gashing their runes / into the bark / scarring trunk / initials standing out / standing tall / for love / beneath curls of incense with unfurled wings / the lovers pronounced / three words each / over the peeling wound / as the tree wept / and the human eyes / remained dry / engrossed in their ritual / establishment / of a lover’s pact / meant to last forever / neither human / able to admit / that forever / doesn’t have to mean eternity / only outlast / those who made the promise / or even shorter—the will to keep it / and i guess in a way / your will could be / what your forever means / but i’m not convinced eternity encompasses / such a small patch of grass / fingers in the soil / homegrown roots / my knuckles are white with grip / nightmares come / to life / i’ve seen them / sketched in crimson / what i can only assume / to be blood / running / beneath spilled milk moonlight / in the hallway that takes / hours to cross / the clocks on its walls / always ahead of me / and my watch / i feel like i’m living / life playing catch-up / three steps behind / and always faltering / always running to get back / to the carving of the beech trees / back to the lovebirds / violence disguised as love / the problem with humans / our tendency for violence / excusable by passion / masked by irrationality / the fragility of human emotion / they say lovebirds have poor sight / poor focus / flighty birds really / their passion is their weakness / and here you know / weakness is just a synonym / just a precursor to downfall / another obstacle to getting / back to those beech trees / the only things that truly matter / unfold beneath shuddering leaves / between scarred trunks / and why do you keep walking past them / as if their suffering is not vocal / earth-shattering / the catastrophic crash / of lost limb after limb / see lovebirds slice / their legacies into the skin of the tree / penetrating that protective layer / the barrier tenderly tended / since the seed casing ruptured / and the sun first graced / the virgin bark / as it stepped into the light / shaking / feverish / starving for worlds / of wind and soil / thirsty / for the elements whirling and crashing / all around / that gaping bark left behind by the / lovers enraptured / each by the other / peeling bark that festers / unlike human skin / the tree is unable to stitch / itself back together / over the wound / and hide / the spillage / the white screaming scar remains / a talisman / a legacy / an invitation to insects / to disease / infestation / and again / redefinition / leads to love as decay / love as downfall / thinning forests / and feathered arms / looped together / bringing about destruction / this hunt / this quest / this path leading nowhere / but deeper and deeper / into the forest / towards the origin of trees / and bees / i just wanted to define love / but i guess i’ll keep walking / keep looking for tracks / trying to recall the penciled path / curled over the torn map / i’ll never leave home again / i’ll never step foot here again / just tell me what it looks like / how it feels / how to recognize love / even bloodied / and heavy with gore / stumbling through the door left unlocked / some nights even ajar / since footsteps echoed down the steps / when love last left / and my maps stopped leading to you.