[[bpstrwcotob]]

Rex

In the summer / we swiped at the sun / laughed until our sides hurt / Brave as kids could be

We're proud to feature this poem from Van G. Garrett’s chapbook Chinaberry Constellations: Odes, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist of The Headlight Review’s 2025 Poetry Chapbook Contest.

Big Mama’s house was two floors

of adventure:

A library of memories

A storehouse of stories

A patchwork of possibilities

Walls with hidden treasure

Creaking steps

A haunted attic

Photos and old records

In the summer

we swiped at the sun

laughed until our sides hurt

Brave as kids could be

Except for when we hard-sprinted

from a German Shepherd

with amber-colored eyes

named after a dinosaur

ACCESS_DENIED: heart.exe

Emotional drive: / fragmented.

> Running diagnostics...

Emotional drive:

fragmented.

Accessing main directory:

/hope/memory/you

Status:

file: touch.exe — missing

file: laugh.wav — corrupted

file: promise.txt — overwritten

folder: trust/ — access denied

Attempting repair...

Error: permission denied.

System prompt:

“Feeling requires vulnerability. Proceed?”

User input:

...

Suggested action:

abort.

Some systems forget

how to open again.

On the Death of a Queen

there is laughter like the ripples / when something dark breaks the water, / the laughter of children colliding

with the inert thigh of their mother / stood hollering

there is laughter like the ripples

when something dark breaks the water,

the laughter of children colliding

with the inert thigh of their mother

stood hollering,

there is the laughter of that discovery

of looking up at the mother’s face softening

and learning fear is a thing

you grow into

not out of,

there is the laughter of wind filling a sail

and two lovers’ hands on the tiller,

peacocks pluming and the dogs’ mistress returning

to a forest of tails around the hearse,

there is

the laughter of doors opened slowly by lovers

with a bottle in one hand and a lie in the other,

then the dark laughter of the same door closing some hours later,

the laughter of disbelief and crumbs in the bed,

there is

the laughter of the town crier drunk in the night

swaying under a lit window

where

the pert whisper of a curtain being drawn

seems louder than the tolling bells.

Scooch

The lower I scooch, the better the reception. / Like the signal’s intensity is what it is except / around me.

The lower I scooch, the better the reception.

Like the signal’s intensity is what it is except

around me. We’re watching The Rockford Files

in my father-in-law’s recreational vehicle in a

private drive in Ft. Lauderdale, James Garner /

Jim Rockford handing out uber-macho lectures.

It’s 1980. I’m a new dad and reading Faulkner

for a class. I catch the politics of calling women

Honey. The woman in tennis whites has framed

Rockford for felony murder. Her navel, an innie,

packs loads of social import before its vanishing.

Arthur Dixon, my kind father-in-law, stands. He

steps to the antenna. Now he’s motioning Scooch,

Jim Rockford smart-mouthing his way to triumph,

the rest of our family inside the house or at church.

This evening, Arthur loves his battery-powered TV,

asks if I like Florida. I say, Positively, as Rockford

calls up William Faulkner in a ’74 Firebird Esprit,

skillfully spinning a steering wheel—like America

is okay just fine but you need to be willing to, well,

scooch down so you catch sight of the road ahead.

Two Paintings

Artist’s Statement

Inspired by René Magritte and Daniel Arsham, I always present contrasting planes of existence in my paintings. To me, “dream” and “reality” are fluid constructs; our perception constantly shifts in response to what we see and feel. This ever-changing perspective is what draws me to art as it also serves as my bridge to empathy. While themes of inequality may not be immediately apparent in my work, they emerge through a hopeful lens, a belief that art has the power to transform how we see and engage with the world. By merging the extraordinary with the everyday, I aim to spark imagination and optimism. What may seem monochromatic to some is a vibrant color in the sky for others, and through my work, I hope to offer that sense of possibility—an invitation to escape negativity and see differently.

Pennypoker1919 to His Followers

Welcome to my playground sanctuary, friends/fans. This room is an extremely passionate and sensual place filled with mystery, desire, masculinity! I am permissive and open, live to be in front the webcam. Please play along and look at the bright side.

Welcome to my playground sanctuary, friends/fans. This room is an extremely passionate and sensual place filled with mystery, desire, masculinity! I am permissive and open, live to be in front the webcam. Please play along and look at the bright side.

My tip menu, dears:

Send me 1 token lol if you enjoy * 2 if you love * 10 for flash my stuff *

30 foreskin massage * 60 explain you my 53 seduction tattoo in ethereal detail *

70 intellectual conversation * 100 special armpit entertainment *

200 open window for view of downtown Kharkiv * 250 confirm theory that I look like

Timothée Chalamet * 500 virtually you sniff my bushy base * 1000 body tour *

1,500 we listen to the air-raid sirens * 3,000 I ship my underwear to your door anywhere *

4,000 seven somersaults in city rubble * 5,000 after the bombs, watch dawn over Kharkiv *

6,000 I introduce you to my hamster * 8,000 intellectual conversation plus *

10,000 become the god of my castle * 20,000 we meet in Kharkiv, you and I, for a night

of body contact only * 40,000 I take you around on my motorbike and you hold me where you

have need to * 50,000 real life body tour + armpit entertainment + bike tour + intellectual

conversation * 100,000 roommate life with you in your country after the war, you house and clothe and feed me and teach me the language and bathe me + unlimited intellectual

conversation + armpit entertainment + long tongue games + every orifice explored + 20 new tattoos *

500,000 I read to you what genre book or mystery you desire, I wash your feet and go for your shopping, we marry, you explore every orifice + intellectual conversation + Maserati convertible + I clean, do house jobs and fixing + unlimited foreskin massage, hundreds of handstands and somersaults

**************1,000,000!************** I belong to you, my every orifice for your curiosity and whim, even after my passing of twink years and you pass into aged years, I feed you, clothe you, bathe you, nurse you and wheel you, and when you’re disappeared I arrange all and inherit all and bring flowers, whichever you command, and keep the earwigs out of vase by your headstone as long as I am able and forever, my love.

Breakout

As soon as you reach a hand through them, / the walls will dissolve.

As soon as you reach a hand through them,

the walls will dissolve. Work with

the window there, above your eye-level.

Even if you have to stand on your toes

until your arches throb, become

a part of what you see through the bars:

the alley where snow hangs on in smears

under bare trees, garbage trucks

pack the sodden refuse, and a grey-striped cat

skirts the puddle under a downspout.

Your window will enlarge until it replaces

the entire wall, and you will walk out whole.

Memory of Exodus

may / these / bones / hold fast / to the / ticking before the / quitting

may / these / bones / hold fast / to the / ticking before the / quitting / we weren’t born a haunting / through numbing or rowdy melancholy / what we inherited meant to drown us / lungs ablaze we gripped / survival continuing as / prophetess spilling radiance / staving disaster determining fate / beyond an algorithm branch / few things are growing / faster from collapse / a dwarf star / uses its energy / before / imploding / our skin was / the night sky / containing / it

final sale: no returns

shelf life / expiration date / say you love me before the price tag peels off

shelf life

expiration date

say you love me before the price tag peels off

[aisle 13, fluorescence flickering—]

you reach for the last dented can of chickpeas & so do i & so we do

& suddenly our delicate hands are tangled like a broken barcode…

like an error in the quick scanner—like a misprint on the receipt of fate.

(does fate even issue refunds?)

the can rolls & gravity takes its tax—bottoms out—bottoms out—out. out. out. we both bend

down, the linoleum yawns. an abyss in the waxy white tiles. (buy one get one free. but

who is one and who is free?) a voice on the loudspeaker crackles: attention shoppers,

all prices are final. but my knees are on clearance—your laughter is marked

down—our shoulders gently brush & suddenly, the barcode of your

wrist is scanning my pulse. i’m full of expired metaphors. you’re

full of unspoken coupons.

(fine print: offers valid while supplies last)

the manager’s voice rustles overhead, a plastic bag in the wind. the fluorescent lights glitch.

the can rolls towards the underworld of the shelves. disappears. the lowest shelf. (where

forgotten things go. where we’re going. where we—) you giggle—you giggle—

you peel the last digit off a price tag and whisper it into my ear like a

prophecy. i mishear it as love. and then all markdowns,

we disappear in the bustling crowd.

(reduced for quick sale)

but then—

i wake up in aisle 13 again. again. again. the same can waiting. you reach. so do i. the scanner

beeps. the loop begins again. (does fate even offer exchanges?) the can rolls—but this time

it doesn’t stop. it keeps rolling, past the lowest shelf, past the waxed linoleum, past

the storeroom door left ajar. down. down into the supermarket catacombs

where carts with rusted wheels hum lullabies and lost items mutters

fainted names. (who is lost? the can? us?) you follow it. i

follow you. a door abruptly closes behind us. the

intercom gives a ding: attention shoppers,

this store is now closed.

and when we returned around—there is no aisle 13…13…13…

no fluorescent light—no way back. only shelves stacked

high with things we do not remember losing. And

shadowy price tags that bear our names.

this item is no longer available.

(final sale. no returns.)

On the 56th Anniversary of My Father’s Death

I decide to join the resistance against negativity. / To celebrate that cancer is a chronic illness now. / And that an old family friend will be able to live / with his blood cancer, stage four.

We’re proud to feature this poem from Elizabeth J. Coleman’s chapbook On a Saturday in the Anthropocene, which was selected by Olatunde Osinaike as a finalist in The Headlight Review’s Chapbook Contest in the Spring of 2025.

I decide to join the resistance against negativity.

To celebrate that cancer is a chronic illness now.

And that an old family friend will be able to live

with his blood cancer, stage four. In my mind,

I bestow on him the joy of knowing his sons’

spouses and children. Then, just as I do every day,

I empty our compost bin into our building's

larger one. Tuesdays the sanitation

department picks the compost up, and, after

a while, the resulting soil will go into New York

City’s parks, or so they say. The songbirds

are returning to Riverside Park, with their

capacity for human speech. My beautiful brown

dove is back, just four feet away, on my office

windowsill, watching me work.

Later we’ll head to Central Park, and, I hope,

come upon the saxophonist playing under

Graywacke Arch. My grandson

will skip over, put money in the case.

Last week, my freckled granddaughter

sold me a hand-painted bookmark

at her Ukraine fundraiser, with pink and blue

flowers, a sun, and a sky of paper white.

And today the woman who owns the frame store

between 95th and 96th on Broadway told me

she wants to go to outer space, as she smiled

from behind the counter in her little shop.

I pictured her en route in her white top,

leopard print leggings and black flats.

Love Song Intended to Stave Off Discontinuation of Relations (Unsuccessful)

I’ll be your boy toy!

Say you want me

And I’ll be your boy toy

If you want me hard to get

I’ll be your coy boy toy

If you want me Scottish

I’ll be your Rob Roy boy toy

If you want me to swell and sway with the crowd

I’ll be your hoi polloi boy toy

If you want me strong like copper and steel

I’ll be your smelted alloy boy toy

If you’re Jewish and I’m not

I’ll be your goy boy toy

If you want me saucy like Szechuan beef

I’ll be your Kikkoman-smothered bok choy boy toy

If you want me After the Thin Man

I’ll be your William Powell and Myrna Loy boy toy

Or, if you want something that melts in your mouth

Slavic and sweet (and you don’t mind

sharing the bed with crumbs)

I’ll be your Bolshoi Ballet/Chips Ahoy! boy toy

Letter from the Managing Editor

As I approach the culmination of my degree, I have gone through various iterations of a capstone idea. Perhaps a collection of short stories, a novel, a novel written through short stories.

As I approach the culmination of my degree, I have gone through various iterations of a capstone idea. Perhaps a collection of short stories, a novel, a novel written through short stories. How many perspectives should I include? Would one be too limiting? Would six be egregious? And, of course, at the crux of it all, the age-old question: what is the story that wants to be told?

Needless to say, it’s been an ordeal trying to figure out the answers, and it would be an understatement to say I have been nervous about all of this. I wanted to start early, get a head start on what I’m aiming for in the fall so I don’t stumble too often. This summer, however, I’ve pivoted much of my energy from capstone prep to my work at The Headlight Review. It’s had me contemplating a great deal about what the submissions we’ve accepted do to grip me, what I can learn from them as I gear up for spelunking the depths of my creativity.

My favorite part of my working on this issue has not simply been copyediting, reformatting, or proofing, but the engagement I have had with the authors, poets, and artists. Corresponding with the person behind the work is my favorite part of any role in editing. If you know the creator, you get to know the piece better, understand the nuance of what they want to say and how they want to say it.

And there I found it. The core of what I need to do to understand my capstone better. And it’s the same invitation that countless literary magazines send to potential contributors: Share a composition that is uniquely yours, that only you could ever create.

Will oil or gouache better convey the way your eyes funnel sunlight? How many characters are needed to express the complexity of your grief? Does the line need to break at a different point to give the impact you desire? The varied and unique answers to these questions are what set each of these pieces apart from the rest.

Captured within this issue of The Headlight Review are three fictional stories, five nonfiction pieces, the visual art of four artists, and the work of a whopping twenty poets, which includes our Chapbook Prize winner and finalists. Each contributor to this issue has a distinct narrative to share, one that only they could ever do justice by sharing it in their own unique voice. It is my greatest hope that you, reader, will absorb each of these pieces with compassion and care, knowing that they, in all their complexity and nuance, came from real people.

To our contributors, I’d like to extend my gratitude for making this experience so enjoyable. To Brittany Files, thank you so much for your guidance toward my start in this role. To the whole THR team, thank you for the warmth with which you’ve welcomed me onto the masthead.

And to our readers, I hope this issue inspires you to walk your stories past the page, your poems through time and space, your art over the edge of the canvas. To share your stories with the world and let them find themselves at home somewhere beyond your mind.

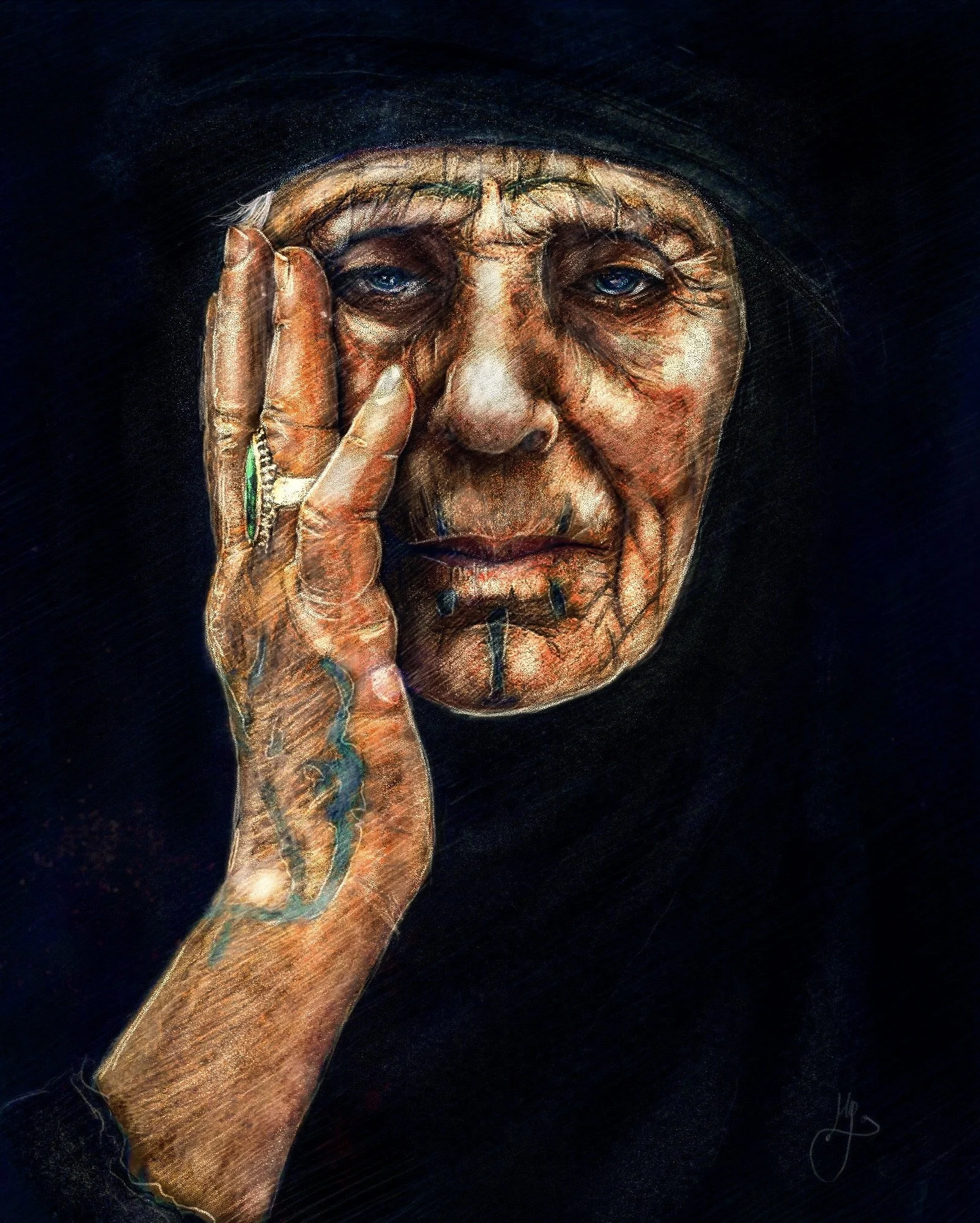

Two Paintings

Artist’s Statement

Gorjian’s work focuses on digital painting, GIS, and urban design, reflecting themes of tradition, identity, and resilience. Through her art, Gorjian aims to bridge past and present, using digital tools to document and celebrate cultural heritage. She has exhibited her work nationally and internationally, engaging audiences in conversations about history, storytelling, and the evolving role of digital media in preserving tradition.

Still Standing

After over fifty years, Warren and I began corresponding—a term I use loosely, as Warren does not write. He does not speak. His IQ hovers below 20, and he does not know who I am.

After over fifty years, Warren and I began corresponding—a term I use loosely, as Warren does not write. He does not speak. His IQ hovers below 20, and he does not know who I am. This is an excuse I saw my parents embrace most of their lives to alleviate the guilt of no contact, of giving up their parenthood, when it came to their fourth child and firstborn son.

Warren was about two years old when it became increasingly evident that something was wrong. He would spend hours sitting on the floor, with his head against the wall, rocking back and forth as if keeping time with the ticking of a metronome only he could hear. His hair had worn a little bald patch in the spot where it met the plaster. Words were not spoken; words were echoed, much like a parrot mimicking what it heard. No words came out of their own accord. No babbling two-year-old banter, the type we parents sometimes complain about. I’m sure there was no complaining by my parents. Only worry. Enough worry to make appointment after appointment with specialist after specialist. Diagnosis: Severe Mental Retardation. Age three.

~

“The Benches” was the place all the mothers of the building would meet with their toddlers and strollers to socialize and gossip. It was a long strip of a park adjacent to Henry Hudson Parkway with benches extending a city block. I remember playing there as a child with dozens of other kids from the building. I have very few memories of my childhood, but “The Benches” I always remember as a safe place. I have had recurring dreams in my adult life of various scenarios where someone is chasing me, trying to kill me, etc. I always knew that if I could just get back to “The Benches” and lay down on the concrete, I would always wake up in my bed. I would be safe.

Mom was embarrassed to have the other moms see her son, who was not quite the average child. So, instead of her usual routine with the older children, of going to The Benches with the other mothers, she would take Warren in the stroller and walk for hours, she told me, so her baby would not be seen, and apparently, she would not be embarrassed. It was the 1950s, but it is still hard for me to fathom.

The doctors, the specialists, and even the Catholic priests would all weigh in. It was decided that the best thing for all would be to place Warren in a home for the mentally ill. The decision was made that Warren, not yet four years old, would be sent to one of the best private institutions in the Greater New York area. I remember driving north, up the tree-lined Saw Mill River Parkway every Sunday afternoon to visit Warren. I was eight.

We would go to the Carvel ice cream stand down the road. Sad but true, this is the only concrete memory I have of my brother. Carvel on Sundays.

To be fair to my parents, it is what you did in the 1950s. Your pediatrician suggested it, and all the specialists recommended it. Many families faced these same choices. For some, it was a deep, dark family secret, not even knowing that their sibling or relative even existed. For others, there would be weekly visits. I know it was not easy for any of them.

My father was manic-depressive in the days before lithium. With three children of my own (all born within twenty-seven months of each other), I have often wondered, what would I have done? There are those who say that the parents were ashamed. Others say they just threw their children away and forgot about them. I do not pretend to know the answer. Unfortunately, what goes up must come down. The mania of my father, along with his record-breaking sales performance, came crashing down. When my father was in a manic stage, he could sell ice to the Eskimos. He was hospitalized, and the income dried up. The private institution had to give way to a state mental hospital, maybe the three most dreaded words in the English language.

Warren was transferred to Willowbrook State Hospital on Staten Island. It was actually called a school, and it was the largest institution for the developmentally disabled in the world at the time (and that was not a good thing).

~

My brother spent about fifteen years of his life at Willowbrook, the place that Robert F. Kennedy called “a snake pit” in 1965. When Kennedy visited the site, he was horrified by what he saw and stated that “individuals in the overcrowded facility were living in filth and dirt, their clothing in rags, in rooms less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in a zoo.”

A combination of budget cuts by Governor Nelson Rockefeller and more demand for placements coupled with indifference led to most of Willowbrook’s problems. Some quote a ratio of seventy patients to two or three caregivers. I wonder how those caregivers could keep clothes on the backs of children with mental disabilities as severe as most residents, who would disrobe as fast as staff could dress them. How could they keep the feces and urine cleaned up when there were seventy other children to look after?

I visited Willowbrook once. It may have been more than once, but the first visit is all I can remember. It was the Fall of 1970. I was twenty years old. I had been visiting my brother from the time I was eight years old. My two sisters, ages 4 and 9, and I, would pack into my parent’s car and drive the half hour or so up the tree-lined highway to Ferncliff Manor in Yonkers. It was a beautiful place with acres of grass. We would lay a blanket out and have a picnic with our brother. We would run around and play, especially my younger sister, as they were the closest, only about a year and a half apart in age. She missed her baby brother.

Willowbrook, on the other hand, was far from the pretty, peaceful picnic grounds of Ferncliff. The antithesis. When I first entered Willowbrook in 1970, I was with my father. My mother would not or could not return. My senses were bombarded. The scent was sharp. A mixture of bleach and feces. The air was still. The halls were dimly lit so as not to see the chaos or the peeling paint. The sounds I could not quite place: murmurs, distant cries, quiet humming, the shuffle of feet. There was a sense of stillness that felt anything but peaceful. I had not prepared myself for what I saw that day, but even then, I had the sense this place was failing the very people it was meant to be helping. A kind of numbness settled in—not because I didn’t feel it, but because I felt too much and didn’t know where to put it.

It wasn’t chaos. It was something softer and harder to bear—indifference. Neglect masked by the very rhythms of daily life.

That day left a lasting mark. It didn’t just shape my view of institutions—it asked me who we become when we are unseen. Does Warren know he has a family? A majority of the residents there have no visitors at all. Unfortunately, I did not pursue those questions or those feelings I had that day, for many years. I buried them with all the rest.

It breaks my heart when I look at this photo taken when Warren was just a few weeks old because I see such hope. Children with such great prospects, immense potential. A future not yet marred by illness and tragedy. We were all unaware of what lay ahead.

It saddens me now because I know the outcome. I lived through it. The memories feel like a slow echo that never quite fades. There would be two more children to come, and the youngest would, in essence, never have the opportunity to know two of her siblings pictured here. In fact, she was not even told of their existence for years.

Lorraine, my older sister on the right would become affected by schizophrenia in her teenage years and commit suicide in 1967. Warren, the newborn in momma’s lap, would be institutionalized by the age of three, and dad, the photographer, unbeknownst to me at the time, would suffer from Manic Depression/Bi-Polar I for the rest of his life. I was sixteen years old when lithium became FDA approved for his type of mental illness. I didn’t fully recognize my family situation for many years. Like all small children, I perceived my life as typical. Of course, it was the only family life I had known. I used to think I had a perfectly normal childhood growing up in an upper-middle-class family in a particularly good neighborhood of the Northwest Bronx. Still, all is not always as it seems.

So, it has been fifty years since that day at Willowbrook. Fifty years of distance is not just a timeline; it’s a slow layering of choices, silences, rationalizations, and even regret. I had always blamed or perhaps rationalized my parents’ behavior for not visiting and for moving 2500 miles away. But what about myself? Was it guilt for not challenging the patterns my parents set? Was the guilt shaped by family dynamics and motional survival?

When you believe someone doesn’t recognize you, especially someone you’re biologically and emotionally tied to, it can feel like the connection was broken before it even had a chance to be made. “What’s the point? He wouldn’t understand. He wouldn’t know me.” But underneath that logic is a powerful current of loss—not just of a relationship, but of significance, visibility, and possibly identity.

Saying “He didn’t know who I was” may have been a way to protect us all from pain. There’s grief for what never existed: no history, shared memories or stories passed between siblings. And that grief is quiet. It just lives silently under decades of rationalization.

~

Since 1985, at the age of thirty, my brother has been living in a group home in upstate New York. The Consumer Advisory Board (CAB) monitors his wellbeing, which provides necessary and appropriate representation and advocacy services on an individual basis for all Willowbrook Class members as long as they live.

Warren has been well taken care of for the past thirty-eight years of his life. He has his own advocate who makes sure that all the stipulations of the Willowbrook Decree of 1975 are being followed when it comes to someone from the Willowbrook Class, as is my brother. But I often wonder, what about the trauma of the past? What does he comprehend of the horrors of growing up in an institution such as Willowbrook?

I am in contact with his advocate as well as his local case worker. They say he seems happy but does tend to withdraw and isolate himself. He doesn’t trust people very much. I suppose I can’t blame him. He is electively mute. Not to mention that Warren is missing the tops of at least six fingers, and, sometime in the past, his nose has been broken. Warren also has no teeth. I read an account of a Willowbrook parent stating that the Willowbrook dentist was notorious for pulling teeth. Her child had no teeth because she would bite herself until she bled. Whether this is connected to Warren’s missing fingers or missing teeth or is a result of abuse or self-mutilation remains a mystery.

~

Warren loves classic rock—a man after my own heart. Music therapy is essential in the lives of the mentally disabled, probably because music is nonverbal. It transcends language. My brother is nonverbal, and I like to think that the music he listens to speaks to him in some way. I know that music calms anxieties and relaxes us when we are overstimulated. I’m told he can spend hours sitting in a rocking chair on the back porch of his group home in Plattsburgh listening to his CDs: He likes everything to be in its correct place, such as furniture being arranged in a particular way, or the house phone hung up in a certain direction. They say he can be quite helpful in clearing things away, such as mats after PT, arranging and clearing the living room after various activities. Sometimes, amusingly enough, his arranging can happen while the activities are still in progress! This brings a smile to my face!

Warren has a personal savings account that cannot accumulate over $2,000. When the account gets up there, they go shopping to spend it down. His basic needs are taken care of, so he can shop for things he especially likes. His caregiver said Warren has the most expensive taste of any man she’s ever met. They will go to JCPenney, and he will go directly to the silk shirts or the most expensive items they sell. He is a very “interesting and complex” person, she says. It shows the respect that he garners as an individual, not simply someone or something to be taken care of. Not forgotten.

~

It had been fifty years since I saw my brother, The last time was that visit to Willowbrook in 1970. Not long after, I left New York for the west coast at about the same time my parents left New York. While my mother was alive, she would get annual reports on his health and progress and always shared them with me.

My youngest sister, Stacey, had never met Warren. He was institutionalized eight years before she was even born. She can’t quite remember when she was told that she had another brother. It was probably when she was about seven or eight years old.

When I brought up my plan, she was hesitant at first, but we finalized our trip and met in Montreal for a three-day visit before driving to Plattsburgh, New York, together in October 2023 to meet our brother. We had also arranged to meet both Warren’s care manager and his advocate from the New York State Office for People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) for lunch in a nearby café.

I was heartened to learn of the care that the State of New York is giving to those with developmental disabilities and the extra care for the “Willowbrook Class.” Meeting these two women in that café was proof enough of the care and concern that my brother is getting. They spent two hours with my sister and me talking about Warren, listening to us recount our own family history, and answering any questions that they were able. They could not have been more caring and sincere. I am so grateful to have met them. Not only did they spend those two hours talking with us, but they also went with us to meet Warren. He was familiar with both, so they carved out even more of their busy days to come along.

We arrived at the house on Turner Road. It was out in the country among the trees. The feeling was peaceful and bucolic. His house manager greeted us and let us know that the other housemates had gone out so that we would have more privacy and less chaos.

There are four male house members. I believe at age sixty-eight, Warren is the oldest. Two of the men are more high functioning and a bit outspoken, while Warren is selectively mute and very low functioning. The fourth member falls somewhere in between, and it all works.

The house manager told us that Warren had just gone to his room to lie down. His advocate went and peeked her head in his room to say, “Warren, you have some company. Do you want to come out and say hello?” No response. His habit is to get into his bed with his legs crossed in a yoga position, then pull the blanket over his head and lie down. He looked like a not so little cocoon. I then said, “Hello Warren, I brought you a present,” and he immediately popped up from his bed and ran down the hall to the dining room table. He moves very quickly (and apparently even quicker when there is a present involved).

A bit later, we went out to his favorite spot on the porch where he sits in his lounge chair to rock and listen to music. We went through his box of vinyl albums sitting next to the record player. I was a bit surprised. I had to laugh and think, He’s a man after my own heart. There was Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, The Beatles (his favorite) and even AC/DC and Metallica!

So, Warren came out of his room to get his present. I brought him a Seattle Sweatshirt, as I know he loves sweatshirts. He went straight to the kitchen to get strawberry milk. The house manager poured his milk and then let him pour in the strawberry syrup and mix it up. They brought it to the table where he gulped it down as fast as he could and some of it spilled down the front of his shirt. All those years at Willowbrook ingrained in him that everyone would steal his food if they could, so eating or drinking as fast as he could was the only way to protect it. To this day, he must have someone watch him eat so the food doesn’t go down too fast and choke him. When a new member of the household is added, Warren will either bring his food to his room or else put his arm around the plate, protecting it from the would-be food thief. Once he is comfortable with the new house member, he will come back to the table for meals. It has been thirty-eight years since Warren left Willowbrook. Habits die hard. I only wish I knew what other horrible memories reside in his brain from spending his most formative years there.

He came to the dining room table and sat across from me.

We looked at each other. There was a connection of some sort. I asked if it was alright to take a picture. His advocate asked Warren if it would be ok, and he immediately jumped up from the table. I thought, oh no, he’s going to run back to his room, and turn back into a cocoon. To my surprise, however, he stood up, went to the middle of the room, and looked right at me, as if to say, “I’m ready for my picture now.” I thought I would quickly take advantage of the situation and handed my phone to Stacey and asked her to take a picture of both of us. I nonchalantly went over and stood next to Warren.

At one point Warren grabbed my arm and started pulling me towards the kitchen. I thought this was a real moment between us, but it turned out, he wanted more strawberry milk. When I realized, I just laughed and said, “Oh, he’s just using me.”

We had a total of twenty minutes or so until Warren decided to go back to his room, get in his bed, and pull the blanket back over his head. Stacey, for the most part, stayed in the background. But I know she was as moved as I was by the whole experience.

He reached out and touched my hand once. I really believe we did have a connection, my brother and I. I now have a new and wonderful memory that is gradually replacing the dark one that haunted me for fifty years.

Excerpt from Salt Bones

An excerpt from Salt Bones by Jennifer Givhan (Mulholland/Little Brown, July 2025)

The Salton Sea,

Southern California

An excerpt from Salt Bones by Jennifer Givhan

(Mulholland/Little Brown, July 2025)

___________________________________________________________________________

Thick, noxious air burns her throat as she flees through the fields, mud clotting to her soles like leeches, one untied shoe after the other over the rutted vegetables.

She shouldn’t run toward the water—it isn’t safe. But the murk would offer cover.

She doesn’t risk a glance behind her or fumble at the yellow onions bulging from the ground. At first, it’s the familiar stench of sulfur bubbling from deep in the earth, mangled with the smell of rotting fish, thousands of carcasses gurgled onto the brackish marsh just ahead.

Then something intoxicatingly sweet fills her nostrils. She’s not near the sugar plant on the other side of town, but those sugar beets smell like overripe dirt anyway. This is more walking into the donut shop at sunrise and ordering a maple bar and sweet tea. She shakes her head, sure her blood sugar’s collapsing from starvation and dehydration and she’s about to nose- dive into the fields when the sweetness sours just as suddenly as it came—and she’s overtaken by the dank stench of sweat and shit.

Her heartbeat throbs in her ears, eclipsing the sound of a truck engine’s roar—another predator in the night, tearing through the furrows and ruining the crops, chasing her.

Would anyone hear her if she screamed?

She can’t waste the breath she needs for running.

In the distance, golden lights twinkle a mythical city arisen in the nowhere between the closest towns, neglected or desolate, and the still-living, breathing town where her people are.

But the lights aren’t magical, and they’re far, much too far. She’d never outrun the truck to get to the geothermal plant where someone at the gate might hear her. Let her in. But would they believe her if she told them who was after her?

A few hundred feet ahead stands a dock. Rickety and slanted, but still possible cover. She could jump into the frothy, stinking water, hold her breath, and hide beneath the battered, salt- crusted planks. Her pursuers might assume she’s darted toward the wildlife preserve, climbed the chain link. Or drowned.

The fug of gasoline and exhaust commingles with the acrid sea, fertilizer, her own sweat and spit, and her blood pumping, pumping furiously. Her lungs scream. Don’t let me die out here—

The sky lights a purple path upward—the Milky Way beckoning as if someone’s holding a flashlight behind a pinpricked cosmic bedsheet. It cascades across the expansive blackness that blurs into the jagged peaks of the Chocolate Mountains beyond this stretch of desert that’s claimed countless lives.

The clomping of hooves and a blaze of headlights pierce her back. Her dark hair flaps crow’s wings against her sweat-drenched hoodie as her high-tops slip against the mud.

There’s nowhere to hide, no tree cover, nothing but shrubs and dirt, and the green fingers of onion bulbs wavering the hands of the dead, reaching for her, grabbing, pulling her downward.

She falls to her knees, blackening her hands with soil.

But the creature canters steadily toward her.

She scrambles up, the Salton Sea in sight, a soupy bog in the darkness.

Her feet crunch fish bones and the minuscule shells of dead crustaceans; millions of them crackle beneath her while she flies toward the pier stretching into the abandoned lake, all that “accidental” water sloshing for miles across the dusty bowl of valle, before the headlights overtake her, and the horse-headed woman cackles, her midnight-black mane scraggling down her bare back.

For a moment, she’s glowing yellow, gleaming with beads of sweat. Saintly.

Then the gunshots resound.

One. Two. The deafening booms reverberate through the mountains. Aerial drills. Only this is no drill. Following the shots—metal clanks its sick click, click. Boom, click, click. Boom.

If anyone were out here but the night animals, the stars, they’ve shut their eyes.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Jennifer Givhan is an award-winning Mexican American and Indigenous poet and novelist from the Southwestern desert. To learn more about her upcoming fourth novel, Salt Bones, from which this excerpt is taken, read our interview with Givhan in conversation with Mary McMyne in the “High-Beams.”

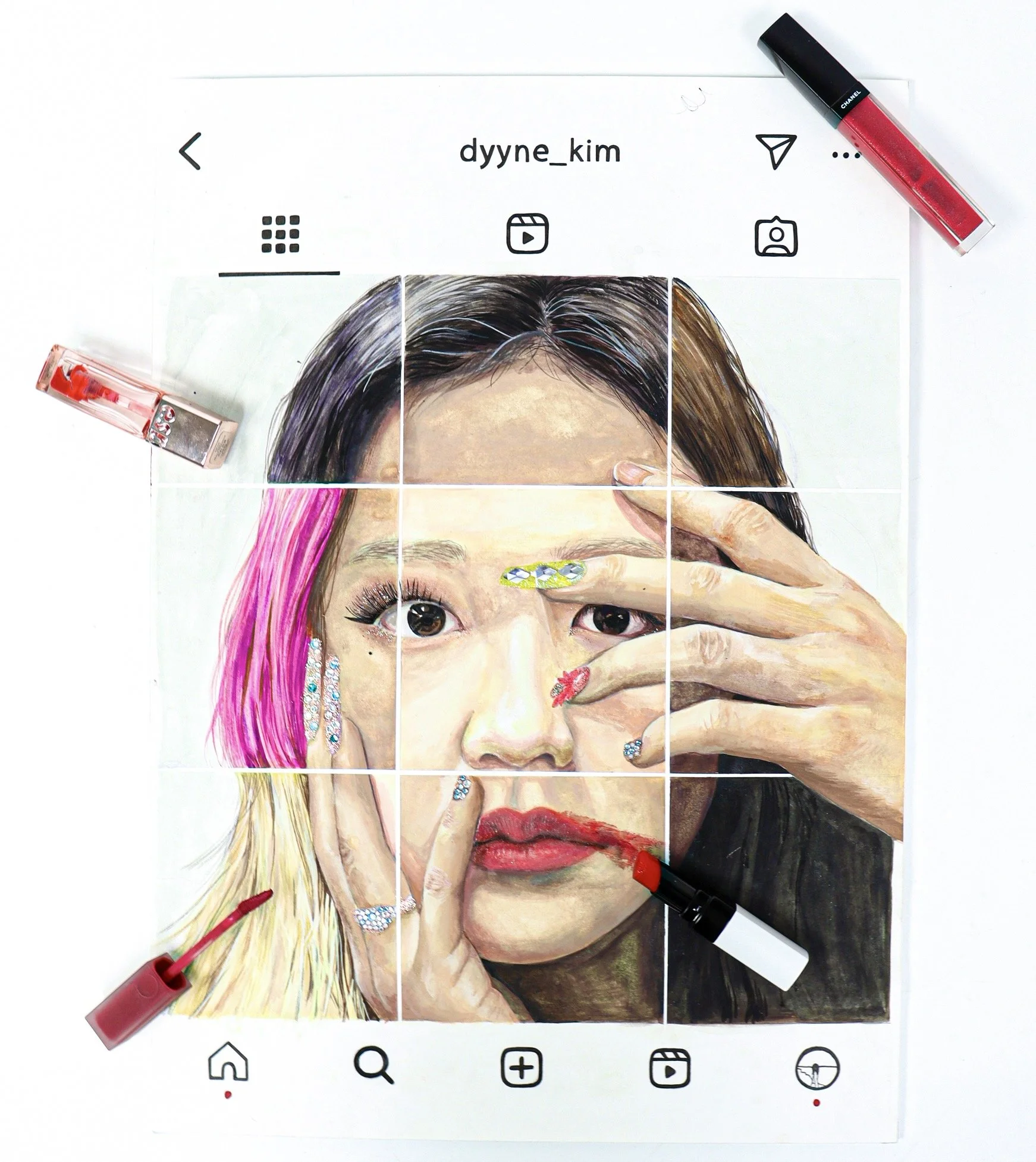

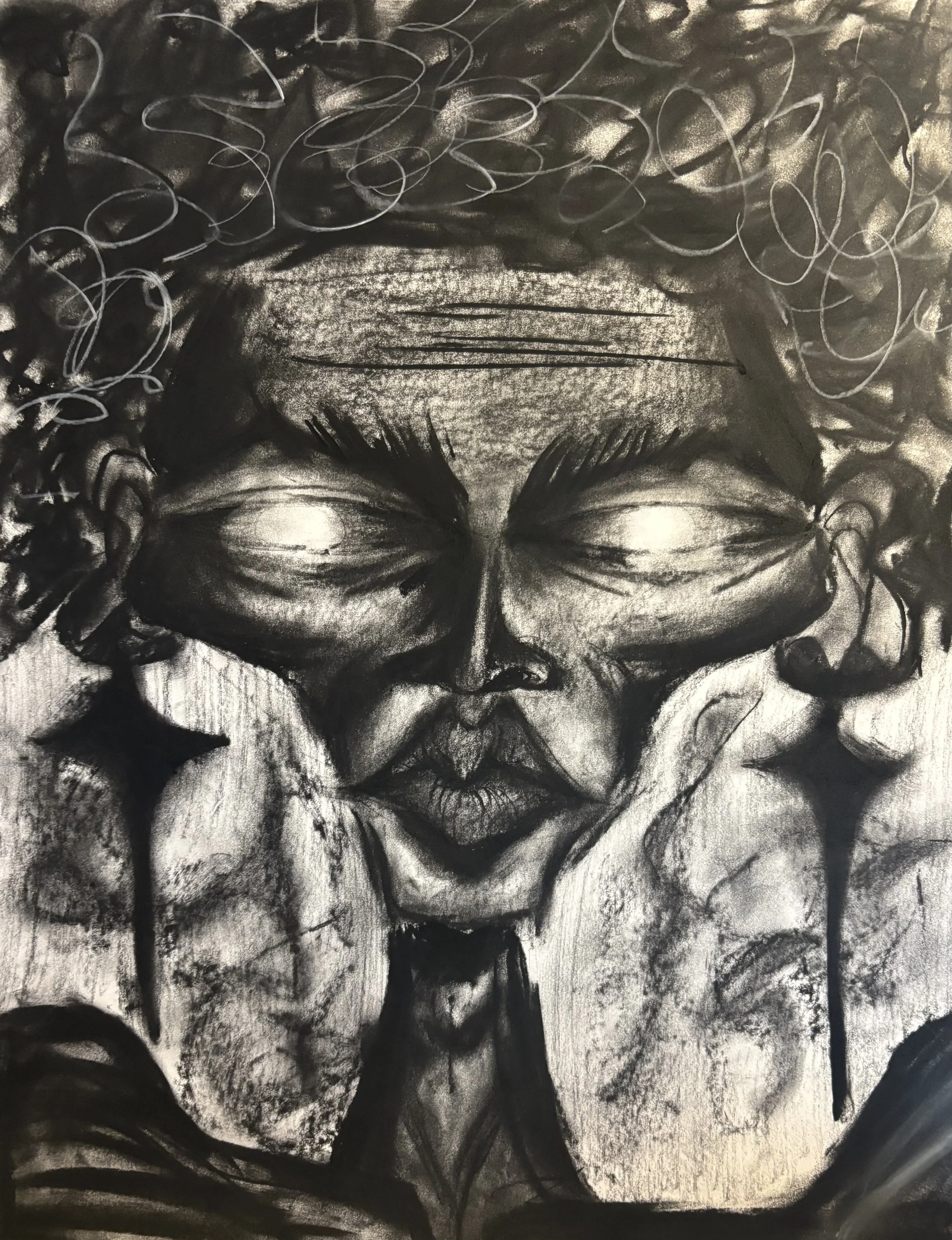

Three Drawings

Artist’s Statement

I believe art is beautiful because it is liberated from any ties to ‘practical’ usefulness or productivity and instead exists only to provide radiance to life. Visual art is an escape from the utilitarian movements people become so accustomed to. I want to visually express what queerness is, find the ideal form, the spirit of queer people, and present it in a way which others can understand the elegance and taste of.

Two Poems

see, the beech tree / never asked to be made palette / for the

lovebirds / armed with blades / gashing their runes / into the bark / scarring trunk / initials standing out / standing tall / for love

it is a burden to know;

it is a given to fear

teeth upon bone. blood upon snow.

skin upon skin. worry upon face.

face upon sheets. repeat then repeat.

bandage the wounds but return to the teeth.

return for more. the wound is not

a badge of the love you once received,

but it feels close enough to warrant

another tear of your flesh, another seep

of your fluids. the wound is not

a badge of the love you once received,

but it is all that awakens your

senses. the days are many but

the moments of awareness are few.

in the morning drops of dew, count

the moments you feared would pass

you by. they already have—maybe.

it is a burden to know. it is a given

to fear. when december comes knocking

at the window, knuckles chapped

in the biting wind, what answers will you have,

what lessons left to share?

someone once told me to understand

love as disease / love as invitation / see, the beech tree / never asked to be made palette / for the lovebirds / armed with blades / gashing their runes / into the bark / scarring trunk / initials standing out / standing tall / for love / beneath curls of incense with unfurled wings / the lovers pronounced / three words each / over the peeling wound / as the tree wept / and the human eyes / remained dry / engrossed in their ritual / establishment / of a lover’s pact / meant to last forever / neither human / able to admit / that forever / doesn’t have to mean eternity / only outlast / those who made the promise / or even shorter—the will to keep it / and i guess in a way / your will could be / what your forever means / but i’m not convinced eternity encompasses / such a small patch of grass / fingers in the soil / homegrown roots / my knuckles are white with grip / nightmares come / to life / i’ve seen them / sketched in crimson / what i can only assume / to be blood / running / beneath spilled milk moonlight / in the hallway that takes / hours to cross / the clocks on its walls / always ahead of me / and my watch / i feel like i’m living / life playing catch-up / three steps behind / and always faltering / always running to get back / to the carving of the beech trees / back to the lovebirds / violence disguised as love / the problem with humans / our tendency for violence / excusable by passion / masked by irrationality / the fragility of human emotion / they say lovebirds have poor sight / poor focus / flighty birds really / their passion is their weakness / and here you know / weakness is just a synonym / just a precursor to downfall / another obstacle to getting / back to those beech trees / the only things that truly matter / unfold beneath shuddering leaves / between scarred trunks / and why do you keep walking past them / as if their suffering is not vocal / earth-shattering / the catastrophic crash / of lost limb after limb / see lovebirds slice / their legacies into the skin of the tree / penetrating that protective layer / the barrier tenderly tended / since the seed casing ruptured / and the sun first graced / the virgin bark / as it stepped into the light / shaking / feverish / starving for worlds / of wind and soil / thirsty / for the elements whirling and crashing / all around / that gaping bark left behind by the / lovers enraptured / each by the other / peeling bark that festers / unlike human skin / the tree is unable to stitch / itself back together / over the wound / and hide / the spillage / the white screaming scar remains / a talisman / a legacy / an invitation to insects / to disease / infestation / and again / redefinition / leads to love as decay / love as downfall / thinning forests / and feathered arms / looped together / bringing about destruction / this hunt / this quest / this path leading nowhere / but deeper and deeper / into the forest / towards the origin of trees / and bees / i just wanted to define love / but i guess i’ll keep walking / keep looking for tracks / trying to recall the penciled path / curled over the torn map / i’ll never leave home again / i’ll never step foot here again / just tell me what it looks like / how it feels / how to recognize love / even bloodied / and heavy with gore / stumbling through the door left unlocked / some nights even ajar / since footsteps echoed down the steps / when love last left / and my maps stopped leading to you.

The Wounded Stork

The dead bird on the front-door step was a barn swallow. Makhosi recognized the copper face and glossy blue hood that continued towards a forked tail. Its clawed feet were tucked together, as if it had been arranged there.

This story won the 2024 Anthony Grooms Short Fiction Prize.

The dead bird on the front-door step was a barn swallow. Makhosi recognized the copper face and glossy blue hood that continued towards a forked tail. Its clawed feet were tucked together, as if it had been arranged there.

It was early and the morning rush had not yet begun, but already the air was unseasonably warm. London, Hotter Than Athens, the newspaper declared. Makhosi glanced up and down the street, as if the mystery of the bird’s appearance could be solved somewhere along their Victorian terrace. The city was hazy with heat. Plane trees lined the pavement, their new leaves, vivid and green, arching against the bleached sky. A black cab idled outside number sixteen and distant traffic rolled like an unseen ocean, punctuated by a muffled yap-yap-yap from behind their neighbor’s door.

“Did the paper come?” Simon nudged alongside her in the doorway. He had tucked his tie away between the top buttons of his collared shirt and carried Jabu in the crook of an elbow. With his dark skin and blonde curls, their son was the perfect, beautiful combination of his South African mother and British father.

“There’s a dead swallow,” Makhosi said and crouched over the bird. Its open eye was as flat and black as a papaya pip.

“Don’t touch,” Simon said and shifted Jabu around his hip, putting his body between the dead bird and the boy. “Lice."

Makhosi tucked her hands into her lap. She’d felt the unexpected softness of a dead bird before. Some time during a barefoot school holiday on her grandmother’s farm in Zululand. Light bones beneath the feathers.

“Probably flew into the window.” Simon tilted his head towards the transom window above their front door where the numbers one and three were sandblasted in the center.

When they’d first viewed the house and Makhosi had expressed reluctance at living at an unlucky number, Simon had dismissed her superstition as “an old wives’ tale.” She knew it was considered good fortune for a barn swallow to nest in your house, but thought better than to wonder out loud what a dead one might portend. She looked up, trying to imagine the trajectory of the small body’s sudden, unconscious drop.

“But it’s perfect, as if it’s been positioned. What if someone rang its neck and left it here?”

“Who on earth would do a thing like that, Max?” There was an edge to his voice.

Dread prickled the back of her neck as Makhosi’s eyes travelled down the row of quiet windows overlooking their street. “I don’t know.”

Simon snapped a stick off the wisteria that draped above the front door and poked the swallow. The jab rolled the bird onto its back. Its neck came to rest at an unnatural angle, exposing the soft triangle of its chin.

“Broken,” he said, as if settling an argument, and handed Jabu to Makhosi. “I’ll get a bag.” He carried the newspaper down the hallway.

Barefoot, Makhosi took the boy up the path to the front gate. As a child, she would watch the high migratory V’s of birds arriving in South Africa each spring, and wonder about the vast northern world they’d traveled from. She’d imagine silent fields of snow running to the horizon like the yellow veld that flowed in all directions across the hills around her grandmother’s farm. Now, from her home in the London suburbs, Makhosi watched the swallows’ seasonal arrival and wondered if they felt regret at leaving the wide blue breath of Africa’s horizons.

This swallow would have flown thousands of miles across the Sahara, via Morocco into eastern Spain, and across the Pyrenees to summer in England. Makhosi glanced back at the bird. The air-bound creature lay incongruous against the earth. It didn’t seem right to simply dispose of the body. It deserved a proper burial. Somewhere in the small garden at the back of their house. Her oasis. Her mother, used to the more expansive suburbs of Johannesburg, referred to London backyards as “postage stamps,” and theirs was no exception, which was precisely why Makhosi loved it. It was neat and manageable, and every plant was there because of a decision she’d made, action she’d taken, and work she’d done. The accident of the swallow’s death and decay should be worth something to the life of a plant, or the soil.

Resolved, Makhosi turned back up the path just as Simon returned with a hand brush and a plastic shopping bag. He bent over the swallow and with a single, surgical movement, swept the bird into the bag and knotted the handles, once, then twice.

The unwelcome image of the bright body decaying to a slow liquid stench inside a sweaty plastic bag flared in her mind. “I was going to bury it!” She was embarrassed by the sudden emotion.

“Now you won’t have to.” Simon moved towards the bins. The bins that would bake in the heat for three days until the garbage men came. He lifted the lid and tossed the lightly weighted bag inside. It landed with a hollow thunk as another swallow darted out from the eaves of their house.

~

Jabu sat on the kitchen floor constructing a cityscape of mismatched Tupperware tubs and lids and cups.

“Swallows migrate to South Africa,” Makhosi said as she tore a banana loose.

Simon pumped soap into his palms and scrubbed his hands. “Sounds like wishful thinking.”

She peeled the banana and pushed a fork through the flesh. “Let’s move.”

“I thought you loved this house.” Simon dried his hands on a dishtowel.

“I love it because you love it.” Makhosi added a spoonful of vanilla yoghurt to the mashed banana and blended the two together. “It’s not the house, it’s more…” she waved the fork in expanding circles, trying to encapsulate the street, the neighborhood, the town, the whole country, “… I don’t know.” She thought of the watchful windows and the dead swallow. A nut of dread rooted in her chest.

“It takes time, Maxie.”

“It’s not a question of time.”

“What is it then?”

“I feel different. I sound different. I am different.” Makhosi and her words ran out of steam. They’d had this conversation before. “It’s hard for me to explain to someone like you.”

“Someone like me?” Simon said under his breath. Then, more loudly, “If you can’t explain, how can I fix it?”

“I don’t expect you to fix anything.”

Makhosi opened the cutlery drawer and piano’ed her fingers across the selection of teaspoons within. Someone like me. She wore her skin, Simon lived in his. But she hadn’t meant to highlight their differences, she only wanted him to recognize how at home he was in the place where she felt lonely. She was a new mother, with a relatively new partner in a new country. She watched other mothers meet for coffee on the local high street, their babies like happy extensions of themselves. They made it look easy. Out of the noise of metal spoons, Makhosi selected the blue plastic spoon Jabu favored. She lifted him onto the kitchen counter, positioned herself in front of him, and offered him scoops of banana and yogurt.

Simon’s phone buzzed.

“I’d better go.” He pulled Makhosi into his chest and pressed his lips against her temple, then stooped to straighten his tie in the reflection of the oven door. “I wish you’d put him in his chair.” He nudged the feeding chair towards Makhosi with his foot.

“He doesn’t like being strapped in.”

“It’s not safe.” Simon’s phone buzzed again, and his thumbs replied.

“We prefer it this way, nê, Jabu?” Makhosi blew a raspberry on the sole of Jabu’s foot. He squealed and grabbed for the spoon.

“If he’s in the chair he can learn to feed himself.”

“Okay, Simon. You do it.” Makhosi put the bowl down and stepped away.

Released from his mother’s ballast, Jabu scooted forward to reach for the spoon.

Simon lunged across the counter. “Christ, Max!” He scooped the boy up and carried him to the feeding chair. Jabu arched his back and began to scream, slamming the spoon—slimy with banana and yoghurt—onto Simon’s tie and clean shirt.

“Fuck!”

“I told you, he doesn’t like it.”

Simon handed the squirming child to Makhosi and snatched a dish towel to mop at his clothes. He unknotted his tie and threw it in the direction of the washing machine. “I’m going to miss my train.” He thumped upstairs.

“Thula, baba, thula,” Makhosi crooned until the boy quietened. She put him on the floor and handed him the spoon.

Makhosi and Simon had met when he’d travelled to South Africa to get experience in the trauma center at Baragwanath Hospital in Johannesburg, where Makhosi worked as a junior nurse. She’d been asked to show the group of young English doctors around the hospital, which had progressed to her showing them around the nightspots of the city, and after working late one night, happily acquainting Simon and his pale, enthusiastic body, with the inside of her bedroom. He’d tugged her dress above her hips and she’d twisted his tie over his shoulder and unbuttoned his shirt until nothing was between them. He’d moved into her flat, and when his work visa expired, he’d asked her to come home to London with him.

Simon’s phone buzzed face down on the kitchen counter. Makhosi flipped it over as a text from Catherine lit up his screen.

– Ready to go? –

Catherine lived next door and was a pharmacist at the hospital where Simon worked. She was one of those girls who liked to be the prettiest in the room. Catherine flirted with men, not because she wanted them, but because she wanted to know that they wanted her.

Simon came downstairs buttoning a fresh shirt, with a clean tie draped around his neck.

Makhosi held up his phone. “Your girlfriend is waiting.”

The mention of their neighbor tuned them both in to the persistent yapping coming from behind the shared wall of their terrace.

“When did she get a dog?” Simon asked.

“Not sure, but it barked all day yesterday.”

He accepted his phone from Makhosi. “She’s applying for a new position and asked me to give her a few pointers.”

“I’m sure she’d love a few pointers from you,” Makhosi said, turning to the dishwasher.

Simon pulled her towards him from behind and slipped his hands under her t-shirt. She sucked in her stomach, conscious of how her body had softened since pregnancy.

“Don’t do that,” he breathed into her neck. “I’m sorry for being a prick.”

“Jabu is safe with me.”

“I know. Of course I know that. I’m sorry.” He ran his hands down to her hips and Makhosi moved against him.

“Not fair,” he groaned. “I really have to go.”

~

Barking followed Catherine out of her front door as Makhosi kissed Simon goodbye at the gate. She was a petite woman. Well-groomed with make-up neatly applied and her bobbed hair freshly blow-dried. Makhosi was abruptly aware of her own unbrushed hair and the baggy t-shirt she preferred to sleep in, now smeared with Jabu’s breakfast. She tugged at the hem, conscious of her loose breasts beneath the thin fabric.

“Hi, Jamie,” Catherine used the anglicized version of their son’s name which Simon said, “made things easier.”

The little boy offered Catherine his spoon. She smiled and gently pushed his hand away. “You’re such a good mom, Max.”

How would you know? Makhosi thought, but said, “Did you get a dog?”

“It’s my sister’s. I’m taking care of it while she moves.”

“It barks a lot.”

“I know. Who knew having a dog was so much work? It's like having a baby!”

Makhosi met Simon’s eye and had to look away. She juggled Jabu from one hip to the other as the little boy jammed the blue spoon into her cheek and then her mouth.

Catherine continued, “I’m trying to find someone to walk her while I’m at work,” and paused—her fingers already moving to slide her house key off the ring.

Makhosi recognized in the pause the expectation of servitude. She was familiar with the expression that accompanied it, eyebrows raised, eyes wide, and lips turned up. She knew how to wait out these encounters. She had done it often enough. With the white women at the playground who assumed she was Jabu's nanny. With the delivery guy who asked, “Is the lady of the house in?” when she answered her own front door. Or the woman in Marks & Spencer who’d asked for her assistance and then seemed annoyed when Makhosi replied, “I don’t work here,” as if Makhosi had knowingly misled her. She held Catherine’s gaze until her neighbor broke with a short cough.

“The back door has a pet hatch so she can get out into the yard, which should help,” Catherine offered an, it’s-the-best-I-can-do shrug.

“We should go,” Simon held up his phone with the time displayed.

The high-pitched bark of the abandoned dog repeated behind Catherine’s front door as she and Simon walked towards the station with their heads angled towards one another. They could easily be mistaken for a couple. Two attractive professionals headed to their important jobs. Catherine’s coat had a slight petrol sheen like the iridescence in a starling’s feathers. An invasive species that must be managed.

Simon looked back.

“Wave to Daddy.”

As soon as they were out of sight, Makhosi lifted the lid off the bin and retrieved the plastic bag with its silent contents.

~

The air inside the house was close and warm, as if the heating had been left on. Makhosi kicked the front door closed and carried Jabu and the plastic bag down the hall to the kitchen.

She and Simon had traveled from South Africa to England via Europe. They’d carried their luggage on their backs and stayed in youth hostels and pensions where they’d made love on rickety beds in thin-walled rooms, with their hands over one another’s mouths. In Rostock, a small town on the Baltic Sea, they’d visited a museum where a white stork was stuffed and displayed, with an 80-centimeter spear through its neck. The wounded stork had been discovered in Germany in the 1840s. The spear that hadn’t killed it was African. The information board had described a time when it was generally believed that birds transformed into mice, or hibernated in lakes or under the sea during winter. The Arrow Stork brought with it the valuable clue that birds migrated unimaginable distances from Europe to central Africa, where, Makhosi imagined, a young hunter had pulled back his arm and let fly his spear at an ethereal creature with an expansive wingspan; a white cutout against the blue paper sky. The stork had borne its unwelcome passenger all the way to Europe. To places the young hunter could not have conceived.

Makhosi took in the pile of laundry at the bottom of the stairs, the rubbish bin jammed with nappies, and yesterday’s newspaper strewn across the counter. Banana smeared on the floor and on the feeding chair. Simon’s ruined tie. Jabu’s toys and books and building blocks tumbling out of multiple soft containers. Tupperware piled on the floor. Dishes in the sink, waiting to be washed, only to be dirtied again. Endless, thankless chores, all underscored by the rhythmic yap, yap, yap from behind the wall, ticking above the heat like a metronome.

Sweat skimmed Makhosi’s temples, pooled beneath her breasts, and pricked her underarms. She hung the plastic bag on the handle of the french doors that opened to the garden, stripped Jabu down to his nappy and laid him in his pram. She yanked off her baggy t-shirt and leggings until she stood only in her underwear. She couldn’t catch her breath. Blood pulsed hot and urgent behind her eyes and for a moment the room tilted and swayed. She unlatched the sash window over the sink and pushed it up, hopeful the air outside would offer relief, but it only brought in the hot dry bark of Catherine’s dog-child. Landing like a hammer blow. Regular, purposeless, thudding against Makhosi’s skull.

She leaned her forehead against the tiled wall, acutely aware of those few cool, hard, square-inches, closed her eyes and imagined taking flight. Disregarding gravity to lift with an imperceptible shift of her shoulders. The brush of feather against feather. To tilt and rise higher and higher into the cool air. To soar and dive. She breathed in. The room righted itself. Makhosi pushed herself up and kicked her discarded clothes towards the washer. Jabu was babbling and drumming the plastic spoon on the side of the pram, completely absorbed in his internal world. She stood for a while, listening to his charming nonsense. The space between the sounds lengthened to the even in and out of his breath. The room expanded. The air felt light. It was quiet, not only inside, but beyond the walls too. Makhosi held her breath. The barking had stopped.

Makhosi stole a quick shower and slipped on a cotton shirt and shorts. She pushed the pram with the sleeping boy into the garden, taking the light plastic bag with her as she went through the french door. Sunshine bleached the sky. Undisturbed by any breeze, the plants and flowers seemed to twitch and shimmer in the heat. She directed the pram into a corner of shade, as deep as it could go, then adjusted the canopy against the light. Jabu slept on. A chaffinch landed on the bird feeder and snapped a sunflower seed in its beak, to peck out the soft nut inside.

The small swallow had left its nest this morning, flicked its feathers, lifted its voice to the new day. She thought of the wounded stork, of the peregrine falcons that hunted through city skyscrapers, the white storks that nested on chimney spires, and the pelicans that lived on the pond in St. James Park.

A clematis waited in a black plastic tub alongside a hole Makhosi had dug the day before. It had begun to flower and searched the air with its blind tendrils for something to grip and climb. Makhosi had dug the hole next to the fence that divided their back garden from Catherine’s, so the clematis could use the slatted wood for support. The flowers had wide, white petals, blushed with lilac tips, which cradled a tighter cluster of purple petals at its centre. A flower within a flower, would make the perfect marker for the swallow’s grave. Makhosi reached into the plastic bag and laid the dead bird on the ground between the fence and the hole, careful to restore its neck to a natural position. She rose to get the hose.

A small, white, curly-haired dog pushed out of the pet hatch and stopped in a rectangle of shade on the terra-cotta paving stones in Catherine’s bare backyard. A lock of fur had been brushed and gathered in a ribbon on top of its head, like a toy you might find in a child’s handbag. It spotted Makhosi and began to bark. The exertion lifted the animal off its feet with a short hop of determination. Bark. Hop. Bark. Hop. Bark. Hop. Not in alarm, but as if it was calling, its brown eyes fixed on hers.

Jabu began to wail.

“Hey, wena, stop that noise.” Makhosi rapped her knuckles on the fence.

The dog rushed over, its entire body shaking with the force of its tail wagging. It shoved its snout through the gap between the ground and the lowest wooden slat, and lapped and licked in excitement and nervous greeting.

“You’re noisy for such a little girl.” Makhosi squatted and reached her fingers through the fence to scratch the dog behind its ears. It pressed into the affection, nuzzling her palm. “Do you miss your mama?”

The animal did an excited dance, twisting its compact body in a tight circle before returning for more. It made a high excited whine, like air escaping a balloon. Makhosi laughed and felt herself soften towards the dog and towards Catherine. Living alone, trying to be helpful to her sister, while making her own way in her career. Maybe she should be a good neighbor and offer to look after the dog? She was here most of the day anyway, and Jabu might like it. She pictured herself pushing the stroller, with the little dog running alongside her through the cow pasture, where the summer herd of ambling bovines with their sharp, grassy smell, grazed on the banks of the Thames.

Jabu continued to cry and Makhosi crossed the small yard to comfort her child, stroking a finger in a slow rhythm between his eyes. The small dog leapt against the fence with excitement, landing both its paws along the lowest strut and barked. Jabu felt hot. Makhosi lifted him out of the pram and bent to the tap where she let cold water run over her open palm, then swiped it around the back of his neck. The little dog yapped and scratched at the fence, pushing its nose into the soil as if to dig its way to them. Jabu calmed as Makhosi walked him around the garden. She hoped to soothe him back to sleep, but he was too distracted by the dog, scratching, whining, digging under the fence.

Makhosi went across to settle the dog, just as the animal darted its small nose under the fence and grabbed the dead bird in its jaws.

For the second time that day, she rushed towards the dead swallow as it was swept away from her. “Stop!” She called for the dog to drop the bird. To release. Release! But it dug in, exposing needle teeth and pink gums behind its blue and copper-feathered prize. Makhosi smacked at the fence with her free hand, until her palm stung, “Let go!” Her skin fizzed with adrenalin and rage.

Jabu began to cry.

Still gripping her son in one arm, Makhosi dropped to her knees and pushed her other arm through the slats of fence. Ignoring the splinters she snatched at the dog’s scruff. The animal jolted its head back, drawing the bird deeper into its mouth to secure its grip. Jabu was crying with the full force of his lungs. She could smell her son’s distress. A mustiness beneath the usual baked dough scent of his skin.

With effort, Makhosi calmed her voice, “Drop the bird. Drop it.”

The dog shook the swallow in its jaws. The defenseless blue head dangled and flinched.

A rage, like a white light, blazed behind Makhosi’s eyes. She clenched her teeth and pushed her left arm further through the slats. In her right arm, Jabu screamed and braced against her body. The dog crouched. Brown eyes stared at her. Its top lip curled back.

“Here, puppy,” Makhosi sang.

The dog replied with a low growl, but took a few slow steps forward. It thought it was a game. Maintaining eye contact with the animal, Makhosi pushed through the fence up to her shoulder. She felt the hot sting of a graze along the tender skin on her inner arm.

“Here, puppy,” she flicked her fingers. “Come to mommy.”

The dog took a few more careful steps, keeping its hold on the bird. Makhosi flicked her fingers again. The dog approached and sniffed at her palm territorially. When it was close enough, Makhosi grabbed the poodle by the scruff of its neck. She expected it to struggle but instead its small body immediately relaxed with some cellular memory of a mother’s gentle jaw carrying its body to safety. She dragged it closer to the fence and secured her grip. Makhosi began to shake the animal back and forth. “Drop it. Drop it!”

Her cheek chafed against the wood. Her shoulder ached and the skin along her arm stung like a burn. Jabu had a fist in her hair and he arched against his mother’s awkward embrace. She closed her eyes and kept shaking. She shook against the empty nests, the lost birds who fly across continents only to mistake a glass window for open sky, the judgement pouring from a dozen careless mouths. Catherine in her petrol-sheen dress which hung from her slim frame, You’re such a good mother, Max. Her own mother, You should raise your child with family, so he learns who he is. The white nurse in the London hospital where Jabu had been born, standing just out of arm's reach as Makhosi struggled to get him to latch on, asking, But isn’t it normal to breastfeed in your culture? Her English mother-in-law, directing her words at a crying Jabu, Poor baby, isn’t your mummy feeding you enough? Simon, this morning, telling her their son should be more independent. Not understanding for one minute how much it hurt for her role in Jabu’s life to be so casually erased.

Makhosi shook until the bird landed on the terracotta tiles in a disarray of wet feathers and clawed feet. She let go of the dog. It backed into the shade, panting hard and watching her with its round brown eyes. Makhosi scooped up the bird and pulled her prize through the fence. She drew her son into her body. Her neighbor’s blank windows leered into her yard. She tilted her head like a crane listening for the whisper of a mouse in the reeds. No bird song and no hum of traffic disturbed the garden. No dog barked. The world was still. Makhosi began to cry.

~

Jabu was asleep upstairs when Simon’s phone buzzed on the arm of the sofa. He stood and walked to the kitchen with his eyes on his screen.

“Catherine didn’t get the job,” he called over water drumming into the kettle.

“She didn’t?” Makhosi followed him to the kitchen.

Simon twisted a knob on the stove and held it down. It clicked until a blue flame erupted beneath the kettle. “Did the dog bark today?”

“It’s just lonely.”

“Tea?” he said.

She nodded.

Simon took two mugs out of the cupboard, tossed a tea bag into each, then crossed to the sink and looked out the window at their back garden.

Makhosi joined him. It was twilight, and a golden glow lit the space like a blessing.

“You planted the clematis.” Simon lifted her hand and kissed her wrist, his breath against her palm. “We can be happy here, Max. Can’t we?”

A pressure wafted off the bridge of her nose, like feathers shaken from a wing. Makhosi leaned against her husband. He smelled of heat and aftershave, underscored by the familiar acidity of hospital disinfectant. Together they looked out at their postage-stamp yard.

The young clematis angled its stem up the fence post.

A Puerto Rican Bathroom

Last St. Patrick’s Day I was groped / on the sidewalk outside Tin Roof. / Too much Jameson was how we got there, / waiting for an Uber / that would never show.

Last St. Patrick’s Day I was groped

on the sidewalk outside Tin Roof.

Too much Jameson was how we got there,

waiting for an Uber

that would never show.

Our best day yet was at Boulder Pointe

Golf Club; I wore two sweaters

and his Patagonia like a dress over top.

Sundays are supposed to be

Mrs. Butterworth’s: warm, and

sweet, and slow.

Last Taco Tuesday a stranger told us

Jesus was gay and poly.

Tipsy on a Maiz margarita, a man

tried to track me and Gabi to our car.

Thank God they noticed; my thoughts

were wandering Maybury Sanatorium

like a drunken jungle gym.

In four days I will be my sister’s Maid

of Honor, in a dress from California, beige

three inch heels from Target.

English is my first language, but

"honor" is an elusive term.

Jeep Cherokees have been following

me everywhere, leaping

out of left turn lanes all over town.

They bring me back to August,

back to Calvin Klein skin,

back to a Puerto Rican bathroom

I will never set foot in.